Rosetta Stone – Artifact That Solves The Riddle Of Egyptian Hieroglyphics

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - A black basalt slab known as the Rosetta Stone was found by a French artillery officer Boussard during Napoleon Bonaparte's Egyptian campaign in 1799.

The artifact thus held the key to solving the riddle of hieroglyphics, a written language that had been "dead" for nearly 2,000 years.

The artifact was discovered among the ruins of Fort Saint Julien, near the town of Rosetta, about 35 miles north of Alexandria, Egypt.

Inscribed with ancient writing, this artifact of great importance came into the possession of the British Government at the capitulation of Alexandria and since 1802 - except for a brief period during World War I - is now preserved in the British Museum.

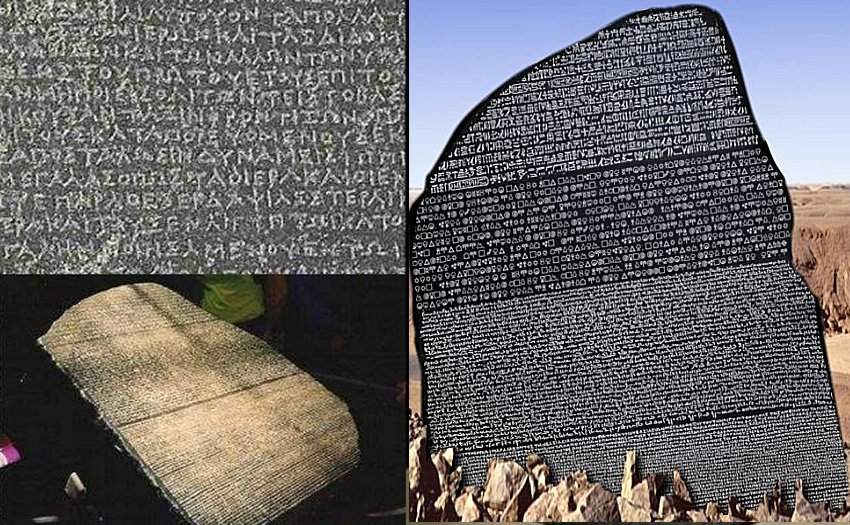

The Rosetta Stone is only a fragment of much larger stele. However, no additional fragments of the artifact were discovered despite several archaeological attempts. As the Rosetta Stone fragment was found in damaged state, none of the three texts that cover it, is complete.

The irregularly shaped stone contained fragments of passages written in three different scripts: Greek, Egyptian hieroglyphics and Egyptian demotic.

The top register of the Stone (Egyptian hieroglyphs) are seriously damaged. Only the last 14 lines of the hieroglyphic text can be seen; all of them are broken on the right side, and 12 of them on the left. The next register (below) of demotic text (Egyptian script related to the Nile Delta) is composed of 32 lines, of which the first 14 are only slightly damaged on the right side. The last register of Greek text contains 54 lines, of which the first 27 survive in full; the rest are increasingly fragmentary due to a diagonal break at the bottom right of the stone.

The ancient Greek on the Rosetta Stone told archaeologists that it was inscribed by priests honoring the king of Egypt, Ptolemy V, in the second century B.C.

More startlingly, the Greek passage announced that the three scripts were all of the identical meanings.

The artifact thus held the key to solving the riddle of hieroglyphics, a written language that had been "dead" for nearly 2,000 years.

It is believed that Rosetta Stone was originally displayed in a temple, and later moved during the early Christian or medieval period. Finally, it was used as a building material in the construction of Fort Julien near the town of Rashid ("Rosetta") in the Nile Delta.

The artifact is the first Ancient Egyptian bilingual text recovered in modern times. The Rosetta Stone gained widespread public interest and many made attempts to translate it. Lithographic copies and plaster casts reached many European museums and scholars.

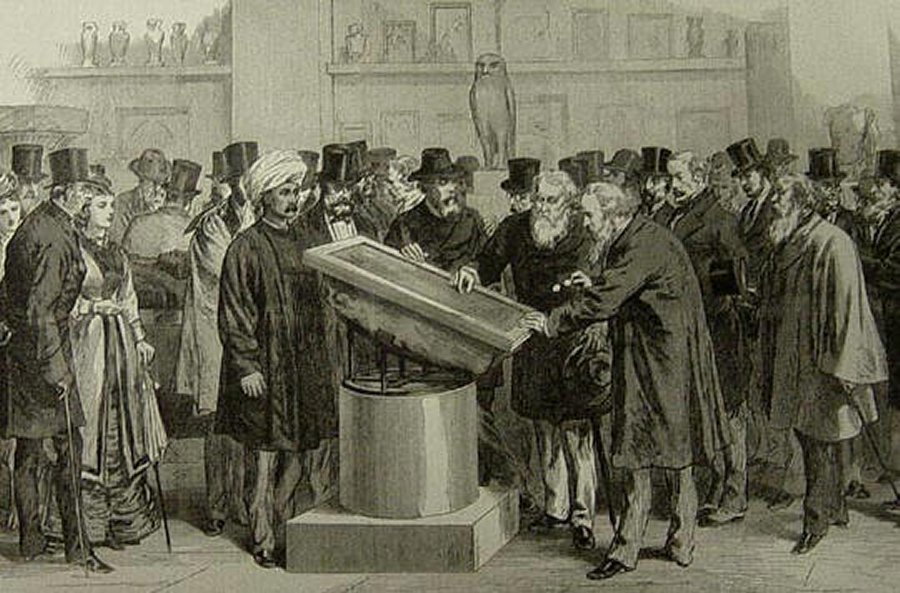

Experts inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the International Congress of Orientalists, 1874 Image credit: The Freeman Institute

In the meantime, British troops defeated the French in Egypt in 1801 and the city of Alexandria capitulated the same year. In this situation, the original Rosetta Stone came into British possession and was transported to the British Museum, where it is displayed since 1802.

Several scholars, including Englishman Thomas Young, made progress with the initial hieroglyphics analysis of the Rosetta Stone. French Egyptologist Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832), who had taught himself ancient languages, ultimately cracked the code and deciphered the hieroglyphics using his knowledge of Greek as a guide.

Hieroglyphics used pictures to represent objects, sounds, and groups of sounds.

Once the Rosetta Stone inscriptions were translated, the language and culture of ancient Egypt were suddenly open to scientists as never before.

The Rosetta Stone is one of history’s most rare finds.

Written by – A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesMore From Ancient Pages

-

Unexplained Accounts Of Mysterious Fires – No Traces But It Happened – Part 2

Featured Stories | Aug 6, 2019

Unexplained Accounts Of Mysterious Fires – No Traces But It Happened – Part 2

Featured Stories | Aug 6, 2019 -

Baffling Sanxingdui Civilization: Why Did These People Have Fascination For Eyes?

Civilizations | Mar 21, 2017

Baffling Sanxingdui Civilization: Why Did These People Have Fascination For Eyes?

Civilizations | Mar 21, 2017 -

Kiln Was Invented In Mesopotamia Around 6,000 B.C.

Ancient History Facts | Mar 7, 2018

Kiln Was Invented In Mesopotamia Around 6,000 B.C.

Ancient History Facts | Mar 7, 2018 -

One Of The Biggest Gold Treasures Ever Discovered In Denmark Is 1,500-Year-Old

Archaeology | Sep 6, 2021

One Of The Biggest Gold Treasures Ever Discovered In Denmark Is 1,500-Year-Old

Archaeology | Sep 6, 2021 -

Cuneiform Tablet With New Indo-European Language Discovered In The Capital Of The Hittites

Archaeology | Sep 21, 2023

Cuneiform Tablet With New Indo-European Language Discovered In The Capital Of The Hittites

Archaeology | Sep 21, 2023 -

Baths Of Caracalla: Italian Antique Thermae Complex For Leisure, Gossip, Business And Socialisation

Featured Stories | Dec 4, 2023

Baths Of Caracalla: Italian Antique Thermae Complex For Leisure, Gossip, Business And Socialisation

Featured Stories | Dec 4, 2023 -

Maori God Pourangahua And His Flying Bird Traversing The Ancient Skies

Featured Stories | Oct 4, 2015

Maori God Pourangahua And His Flying Bird Traversing The Ancient Skies

Featured Stories | Oct 4, 2015 -

Two 1,800-Year-Old Sarcophagi Of Wealthy People Accidentally Found At Ramat Gan Safari Park

Archaeology | Feb 22, 2021

Two 1,800-Year-Old Sarcophagi Of Wealthy People Accidentally Found At Ramat Gan Safari Park

Archaeology | Feb 22, 2021 -

Many Samurai Had Swords With Secret Crucifixes And Hidden Christian Symbols To Avoid Persecution

Ancient History Facts | Jan 10, 2017

Many Samurai Had Swords With Secret Crucifixes And Hidden Christian Symbols To Avoid Persecution

Ancient History Facts | Jan 10, 2017 -

A 2,500-Year-Old Marble Disc, Designed To Protect Ancient Ships And Ward Off The Evil Eye – Discovered

Archaeology | Aug 4, 2023

A 2,500-Year-Old Marble Disc, Designed To Protect Ancient Ships And Ward Off The Evil Eye – Discovered

Archaeology | Aug 4, 2023 -

Secrets Of Mysterious Bronze Age Hoard Found In Rosemarkie, Scotland Revealed

Archaeology | Jul 31, 2024

Secrets Of Mysterious Bronze Age Hoard Found In Rosemarkie, Scotland Revealed

Archaeology | Jul 31, 2024 -

Ancient Graffiti Unearthed At Roman Vindolanda Reveals What One Roman Thought Of Another

Archaeology | May 27, 2022

Ancient Graffiti Unearthed At Roman Vindolanda Reveals What One Roman Thought Of Another

Archaeology | May 27, 2022 -

Ancient Highways Unearthed In Arabia

Archaeology | Jan 14, 2022

Ancient Highways Unearthed In Arabia

Archaeology | Jan 14, 2022 -

Valentine’s Day’s Connection With Love Was Probably Invented By Chaucer And Other 14th-Century Poets

Ancient Traditions And Customs | Feb 14, 2023

Valentine’s Day’s Connection With Love Was Probably Invented By Chaucer And Other 14th-Century Poets

Ancient Traditions And Customs | Feb 14, 2023 -

Movie Stars’ Creepy Encounters With The Unexplained

Featured Stories | Oct 28, 2019

Movie Stars’ Creepy Encounters With The Unexplained

Featured Stories | Oct 28, 2019 -

Bes: Egypt’s Intriguing Dwarf God Of Music, Warfare And Protector Against Snakes, Misfortune And Evil Spirits

Egyptian Mythology | Jul 31, 2016

Bes: Egypt’s Intriguing Dwarf God Of Music, Warfare And Protector Against Snakes, Misfortune And Evil Spirits

Egyptian Mythology | Jul 31, 2016 -

Sarcophagus Of Pharaoh Ramesses II Found In Abydos, Egypt

Archaeology | May 29, 2024

Sarcophagus Of Pharaoh Ramesses II Found In Abydos, Egypt

Archaeology | May 29, 2024 -

On This Day In History: He Wanted The Bible To Be Available To All – Burned At The Stake On Oct 6, 1536

News | Oct 6, 2016

On This Day In History: He Wanted The Bible To Be Available To All – Burned At The Stake On Oct 6, 1536

News | Oct 6, 2016 -

On This Day In History: Munich Agreement Was Signed – On Sep 30, 1938

News | Sep 30, 2016

On This Day In History: Munich Agreement Was Signed – On Sep 30, 1938

News | Sep 30, 2016 -

Cooking In Indus Valley – Leftovers In Prehistoric Kitchen’s Vessels Analyzed

Archaeology | Mar 24, 2022

Cooking In Indus Valley – Leftovers In Prehistoric Kitchen’s Vessels Analyzed

Archaeology | Mar 24, 2022