A newly discovered tablet V of the epic of Gilgamesh. The left half of the whole tablet has survived and is composed of 3 fragments. The Sulaymaniyah Museum, Iraq. Photo © Osama S.M. Amin.

Ιt’s not unusual for fantasy epics to endure for years. But even George R.R. Martin would be shocked to learn about the century-and-a-half wait for a new chapter of the Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the world’s oldest written stories.

The Sulaymaniyah Museum in the Kurdistan region of Iraq has discovered 20 new lines to the ancient Babylonian poem, writes Ted Mills for Open Culture.

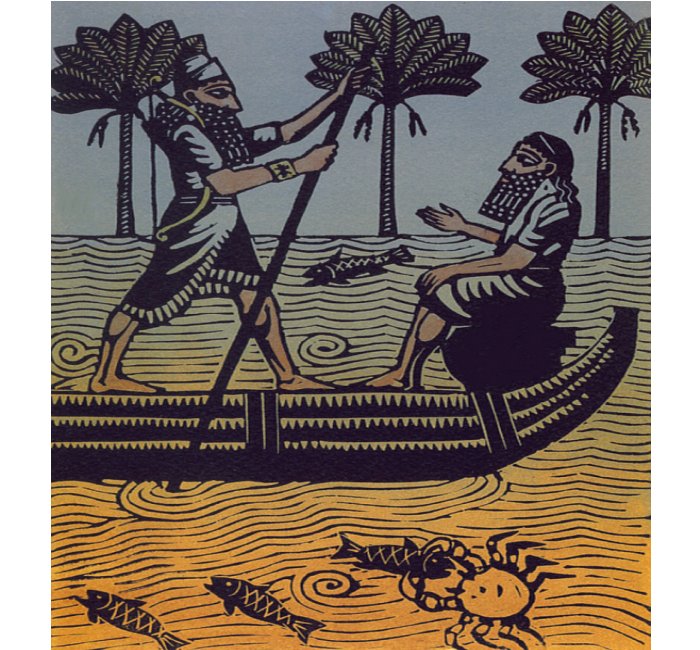

Illustrations by Francis Mosley, translation Andrew George, The Epic of Gilgamesh, Folio Society, 2010

The Epic of Gilgamesh, which dates back to 18th century B.C., was pieced together from fragments that tell the story of a Sumerian king who travels with a wild companion named Enkidu. As Mills explains, scholars were well aware that new fragments of the poem could possibly turn up — modern readers are most familiar with a version discovered in Nineveh in 1853 — and during the war in Iraq, as looters pillaged ancient sites, they finally did.

The collection was composed of 80-90 tablets of different shapes, contents and sizes. All of the tablets were, to some degree, still covered with mud. Some were completely intact, while others were fragmented. The precise location of their excavation is unknown, but it is likely that they were illegally unearthed from, what is known today as, the southern part of the Babel (Babylon) or Governorate, Iraq (Mesopotamia).

The tablet is three fragments joined together, dating back nearly 3,000 years to the Neo-Babylonian period. An analysis by the University of London’s Farouk Al-Rawi’s reveals more details from the poem’s fifth chapter, according to Amin.

The new lines include descriptions of a journey into the “Cedar Forest,” where Gilgamesh and Enkidu encounter monkeys, birds and insects, then kill a forest demigod named Humbaba. In a paper for the American Schools of Oriental Research, Al-Rawi describes the significance of these details:

The previously available text made it clear that [Gilgamesh] and Enkidu knew, even before they killed Humbaba, that what they were doing would anger the cosmic forces that governed the world, chiefly the god Enlil. Their reaction after the event is now tinged with a hint of guilty conscience, when Enkidu remarks ruefully that … “we have reduced the forest [to] a wasteland.”

The museum’s discovery casts new light on Humbaba, in particular, who had been depicted as a “barbarian ogre” in other tablets.

As Mills writes, “Just like a good director’s cut, these extra scenes clear up some muddy character motivation, and add an environmental moral to the tale.”