A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - In the mountains of the Syrian desert - covered with with unknown rock formations, stone circles and mysterious lines of stone - there is an ancient monastery with ancient tombs, corridors and walls covered with frescoes.

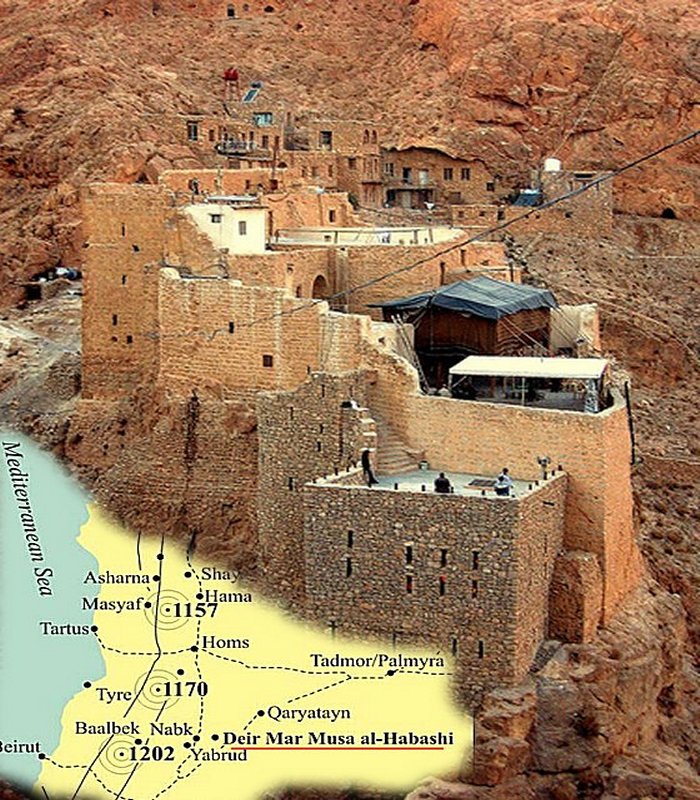

Located 90km north of Damascus, the monastery is named after St. Moses the Abyssinian - Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi.

Unusually, the monastery survived the uncertainties around the incorporation of Syria into the Islamic world in AD 634-635, and also the Crusades from 1098 onwards.

Analysis of fragments of stone tools found in the area suggests the rock formations are much older than the monastery, perhaps dating to the Neolithic Period or early Bronze Age, 6,000 to 10,000 years ago.

In Western Europe megalithic construction involving the use of stone has been dated to as early as ca. 4500 BC. This means that the Syrian site could well be older than anything seen in Europe.

But to conduct archareological research in such region is not an easy task because the political conflict is tearing apart the Middle Eastern nation.

Archaeologist Robert Mason spoke at the Semitic Museum about the discovery of mysterious rock formations near the Syrian monastery Deir Mar Musa (above), and the need for further exploration. Photo Credits: Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

A few years ago, archaeologist Robert Mason of the Royal Ontario Museum was at work at an ancient monastery when, walking nearby, he came across a series of rock formations: lines of stone, stone circles, and what appeared to be tombs.

Dr. Mason's archaeological fieldwork has been based in Syria since 1998, particularly in the citadel of Aleppo, and since 2004 at the monastery of St. Moses (Deir Mar Musa).

The monastery, 90 km north of Damascus in the mountainous Syrian desert, is the focus of his survey of the site and its environs, recording features possibly as early as the Neolithic.

Research at the monastery has led to a growing research interest in the archaeology of Christianity and monotheism generally in the Holy Land.

However, much more detailed examinations are needed to understand the structures, according to the researcher. Moreover, Dr. Mason is uncertain when he will be able to return to Syria, if ever.

The region is dry today (“very scenic, if you like rocks,” Mason said), but was probably greener millennia ago.

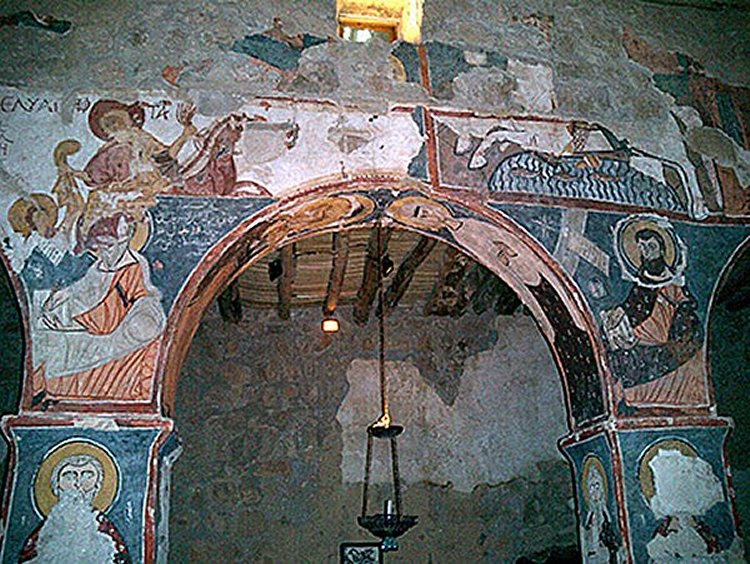

The monastery is home to many frescoes — some badly damaged— depicting Christian scenes, female saints, and Judgment Day

It was clear, Mason said, that the purpose of the stone formations was entirely different from that of the stone-walled desert kites.

The kites were arranged to take advantage of the landscape and direct the animals to a single place, while the more linear stone formations were made to stand out from the landscape. In addition, he said, there was no sign of habitats.

Frescos of the Last Judgment in the church of Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi or Monastery of Saint Moses the Abyssinian, Syria Credits: Bernard Gagnon

“What it looked like was a landscape for the dead and not for the living,” Mason said. “It’s something that needs more work and I don’t know if that’s ever going to happen.”

Deir Mar Musa (or the Monastery of Moses the Abyssinian), is a remote place. Clinging to a mountain precipice in west-central Syria, it’s reached via a dusty 80km taxi or bus-ride from Damascus; the last connecting to a car at the thirsty, desert-edge town of Nebek.

The monastery is home to many, remarkable 11th century frescoes — some badly damaged— depicting Christian scenes, female saints, and Judgment Day.

Trace of the site’s many layers of history had been preserved, perhaps most importantly the chapel itself, built by the eponymous Moses; a 6th century Abyssinian king who first gave up worldly pleasures to become a monk in these inhospitable hills.

In a talk in 2010, Mason said he felt like he’d stumbled onto England’s Salisbury Plain, where Stonehenge is located, leading to the formations being dubbed “Syria’s Stonehenge.”

Mason also talked about the monastery, Deir Mar Musa. Early work on the building likely began in the late 4th or early 5th century. It was occupied until the 1800s, though damaged repeatedly by earthquakes.

Following refurbishment in the 1980s and 1990s, it became active again.

Mason thinks the monastery was originally a Roman watchtower that was partially destroyed by an earthquake and then rebuilt.

The compound was enlarged, with new structures added until it reached the size of the modern complex, clinging to a dry cliff face in the desert about 50 miles north of Damascus.

Mason was searching Roman watchtowers when he came across the stone lines, circles, and possible tombs.

He also explored a series of small caves that he believes were excavated and lived in by the monks, who returned to the monastery for church services.

Mason said that if he’s able to return, he’d like to excavate the area under the church’s main altar, where he thinks there might be an entrance to underground tombs. He’s already received the permission of the monastery’s superior, who was recently ejected from the country.

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com