On This Day In History: “Man In The Iron Mask” Died In The Bastille, Paris, France – On Nov 19, 1703

AncientPages.com - On November 19, 1703, "the man in the iron mask" died in the Bastille in Paris, France. He was buried under name "Marchioly," and his age was "about 45."

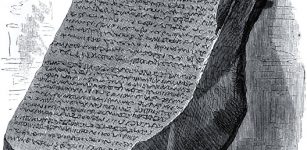

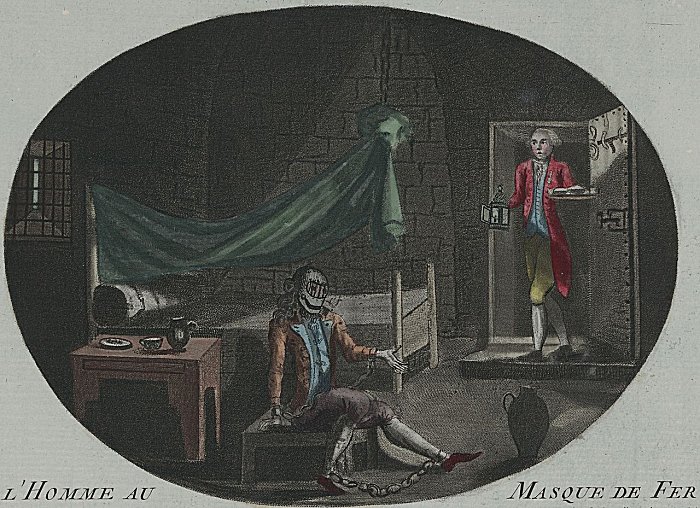

The Man in the Iron Mask, etching and mezzotint, 1789. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

The Man in the Iron Mask, etching and mezzotint, 1789. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.

He was a political prisoner during the reign of Louis XIV of France (1643–1715), and he was famous in French history and legend.

There is no historical evidence that the mask was made of anything but black velvet (velours), and only afterward did legend convert its material into iron. According to sources, his captors said to treat him with respect but kill him when he tried to talk about his identity.

The mysterious man was arrested in 1669 or 1670 and held in several French prisons, including the Bastille and the Fortress of Pignerol (modern Pinerolo, Italy).

According to recent research, his name might have been "Eustache Dauger," but this has not been proven.

The man's identity in the mask was already a mystery before his death. Many different suggestions have been proposed. However, only two prisoners were in custody during the same time as the "man in the iron mask": Ercole Matthiole and Eustache Dauger.

Matthiole was an Italian count who was abducted and jailed after he tried to double-cross Louis XIV during political negotiations in the late-1670s. He was a longtime prisoner, and his name is similar to "Marchioly."

It is generally agreed, however, that Matthioli died in the Îles Sainte-Marguerite in April 1694. The second, even more convincing candidate was Eustache Dauger, a valet, who was arrested on his orders for an unknown reason near Dunkirk in July 1669.

Based on the correspondence of Louis XIV's minister Louvois, jailers were instructed to restrict Dauger's contact with others and to "threaten him with death if he speaks one word except about his actual needs." Dauger was frequently transported from one prison to another; for some reason, the precaution of the mask was necessary to keep absolute secrecy regarding this person.

What little is known about the enigmatic prisoner stems chiefly from contemporary documents that came to light during the 19th century.

These records, primarily comprising some of the correspondence between Saint-Mars, the prison governor, and his superiors in Paris—initially Louvois, Louis XIV's secretary of state for war—provide a glimpse into the life and circumstances surrounding this mysterious figure.

The documents disclose that the prisoner was referred to dismissively as "only a valet" and had been incarcerated due to actions related to his employment prior to his arrest. Intriguingly, legend maintains that no one ever glimpsed his face because it was perpetually concealed by a mask crafted from black velvet cloth—a detail sensationalized by Voltaire into an iron mask.

Official records clarify that this covering of the face was mandated only under specific conditions: when the prisoner traveled between different prisons after 1687 or while attending prayers within the Bastille during his final years of confinement.

Modern historians believe that such measures were implemented by Saint-Mars not out of necessity but rather as a means to augment his own prestige and mystique.

By cultivating an aura of mystery around this seemingly significant yet shadowy figure, Saint-Mars inadvertently fueled enduring rumors and intrigue about a prisoner whose true identity has remained elusive through centuries of speculation and myth-making. Many pondered whether there might have been more than met the eye regarding this obscure "valet," whose masked presence still captivates historical curiosity today.

It is still unclear who the mysterious man was and if his name was a pseudonym; it was suggested that he was a failed assassin, the twin brother of Louis XIV, and a man involved in a political scandal.

AncientPages.com

Expand for references