Death And Afterlife In Sumerian Beliefs

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - Our knowledge about the Mesopotamian afterlife beliefs comes from literary texts recorded on cuneiform clay tablets and most of this material is Sumerian.

According to the Sumerian belief, after death, people would take a journey to the Underworld, a gloomy and unpleasant realm.

Underworld was not a pleasant realm of existence, a dark, dusty land, where the bread did not taste good, their garments were only feathers to protect them from the cold, and water to drink was brackish.

Many different graveyards have been unearthed and they give us an idea about how the Sumerians lived and died.

Sumerians respected death and when life came to an end, they took the burial of the dead as seriously as people in other cultures.

However, the Sumerians had no cemeteries except for the king and his most important nobles. In Sumer tradition, the body was frequently buried in the family tomb within the house. The body was usually laid to rest curled up and placed in a large jar, a casket, stone sarcophagus, or simply ordinary cloth wrapping. Whether the burial was lavish or rather poor depended mostly on the economic status of the deceased.

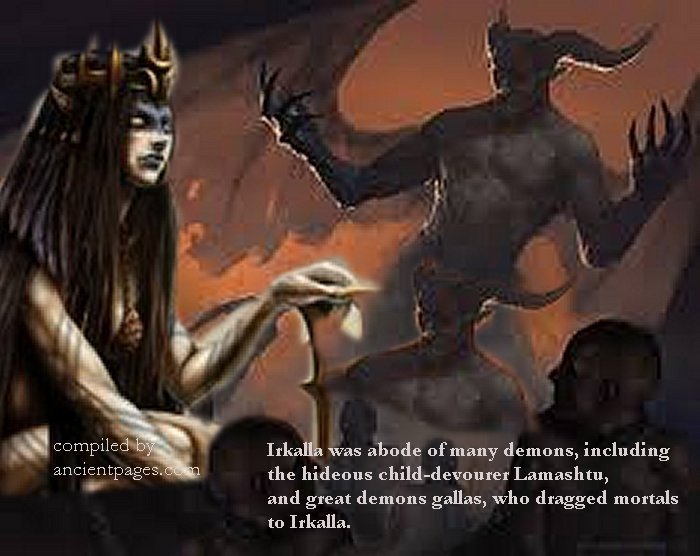

In Babylonian mythology, Irkalla was the underworld from which there was no return - read more

All poor deceased were buried with the possession they mostly treasured in life; rich ones usually went on their journey to the afterlife with grave goods specially prepared for their burial.

Most impressive and valuable grave goods have been revealed in excavations of royal burial sites.

One of the most spectacular and relatively untouched by robbers was the tomb of a mysterious Queen Puabi with some beautiful objects such as gold ribbon headdresses, a wooden lyre, a beautifully decorated royal sled, precious jewelry, and a large number of slaves and servants who were sacrificed to accompany Puabi on her journey to the afterlife and serve her there, as we described in our article about Puabi.

What Was Sumerian View Of The Underworld?

This view was definitely gloomy. It was not a pleasant realm of existence, a dark, dusty land, where the bread did not taste good, their garments were only feathers to protect them from the cold, and water to drink was brackish.

In her book “Sumer and the Sumerians”, Harriet Crawford writes that “based on evidence, there is the impression that their condition in the underworld reflected their social status on earth, not their virtue. Goods that people took to their graves were considered comforts that they could take with them into the afterlife. When a king died, people who worked for him and many of his possessions were buried with him, including wagons and animals.”

Most Sumerian people lived hard lives, and their ideas about the afterlife resembled their earthly existence so they "wasted no time" preparing for the afterlife. Man - as the work of the gods – had a soul, which after the death of the body, continued to this sad, underground realm of the goddess Ereshkigal, the sister of Inanna (Ishtar).

An interesting concept of sin and punishment existed among people of Mesopotamia, but it only related to earthly life and therefore it could be prevented by confession, sacrifices, and prayers. Interestingly, these people were extremely conscious of their sinful nature so they frequently asked for their deity for forgiveness:

"O goddess whom I know or do not know, (my) transgressions are many; great are (my) sins. "The transgressions which I have committed, indeed I do not know; "The sins which I have done, indeed I do not know…”

"O god whom I know or do not know, (my) transgressions are many; great are (my) sins…”

The existence of the soul in the afterlife, on the other hand, depended only on the splendor of the burial and sacrifices submitted by the family to the deity.

Babylonians Believed In Judgment In The Afterlife

The Babylonians (including also the Assyrians and the Sumerians) believed in judgment in the afterlife.

Accompanied by seven judges sitting in front of her, Ereshkigal, the goddess of the underworld presided over the dead, and the sentence of death was announced when the deceased the underworld.

According to the Sumerian poem "Gilgamesh, Enkidu, and the Nether World," mortals were also allowed to enter the realm of death but they had to follow certain rules, for example, they were not allowed to wear clean clothes, carry a weapon and make noise, among other things. Breaking any of these rules resulted that the person was forever submitted to the world of shadows and not allowed to return.

We can cite Gregory Shushan, in his “Conceptions of the Afterlife in Early Civilizations”, who gives an example of what Enkidu - EN.KI.DU ("Enki's creation"), a central figure in the "Epic of Gilgamesh" - saw in the realm of the dead:

“…Enkidu reveals how the man with one son weeps because of the loss of his home. The man with two sits on bricks and eats bread. The man with three drinks water from a skin on his saddle, while the man with four, rejoices ‘like a man who has four donkeys’. The man with five, is allowed entry into the palace, ‘like a fine scribe’… The man with seven, sits on a throne with the gods and hears proceedings/judgements. Those with no heir eat bread like bricks. …”

“The man who died in battle has his head cradled by his parents, while his wife weeps. Those without funerary offerings eat crumbs and table scraps. The man who died an early death lies ‘on the bed of the gods’. The man who was burned to death rises to the sky: ‘his ghost was not there, his smoke went up to the heavens’...

Apparently, Sumerians, Babylonians, and Assyrians did not believe that something good was waiting for them on the other side. They did not believe it was worth wasting time to prepare for the afterlife. Ancient Egyptians' beliefs in death and the afterlife were different, and they prepared for their journey to the other side.

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references