Struggle To Get Mail On Time Has Lasted More Than 5,000 Years – Part 2

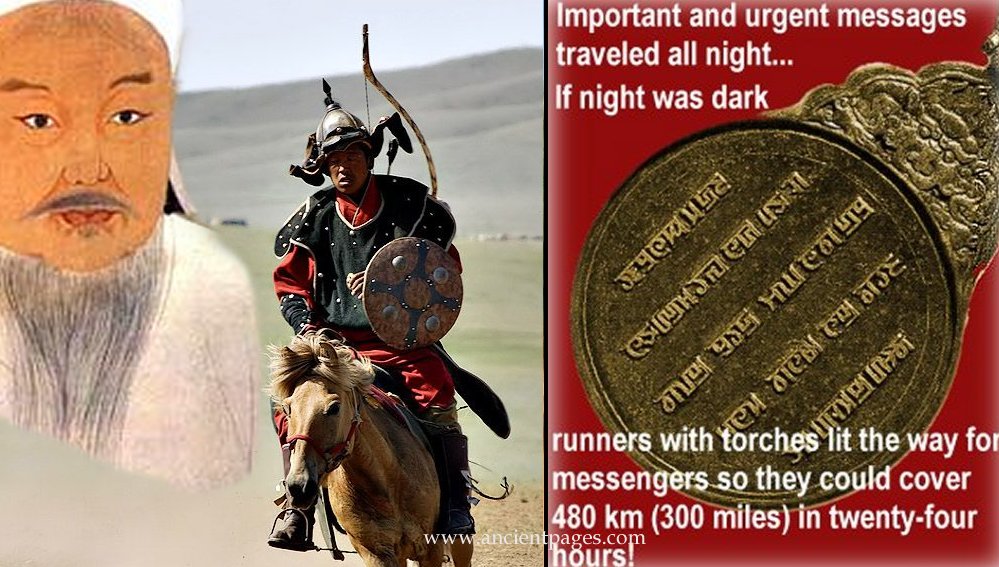

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - Mongolian messengers had to travel 48 kilometers (30 mi) a day and being in a possession of a "magic" badge (see left image) they could get the help they needed on their long way between post stations located across Mongolia's endless steppes.

During his travel throughout Mongolia in the 1200s, the great explorer Marco Polo, came in contact with the Mongolian postal services. He was impressed with what he saw.

The great khan's messengers galloped on swift horses along this amazing network of roads. Every 40 km (25 miles), they reached a post station with fresh horses ready to start their journey.

"To speed communications within the empire," Diane Childress writes in her "Marco Polo's Journey to China", the Mongols built or repaired roads and canals. They planted trees, or they piled tall towers of stones along the roadsides in desert areas to mark the way.

The great khan's messengers galloped on swift horses along this amazing network of roads. Every 40 km (25 miles), they reached a post station with fresh horses ready to start their journey.

As Marco Polo reported, "the messengers manage to cover 250 miles (400 km) each day and bring news and letters to the great Khan." The most important and urgent messages traveled during night time. If night was very dark and without the moon, runners with torches lit the way so messengers could cover 480 km (300 miles) in twenty-four hours.

The whole system was perfectly organized and Mongolia can pride itself on developing one of the world’s first long-distance internal postal systems and it took place during the time of Djingis Khan.

Each city and town supplied and maintained the horses. They rotated half of the herd every month from the post station to pastures so that rested and well-fed steeds were always available. At every large river or lake, the Mongolian towns had several boats ready to ferry messengers across.

Towns on the edges of deserts had food and water for messengers to take with them!

This impressive and perfectly functioning system called "yamb" (in Mongolian) also included foot runners who ran between post stations 5 km (3 miles) apart carrying less important messages or packages.

The runners wore belts equipped with bells, of which noise was heard and announced a runner's approach so that the next runner could prepare to take over the mail as soon as the first one reached his station.

Mongolia's postal service was very similar to that established in China, where 1400 courier stations scattered across the vast country, were ready to serve working messengers both day and night. The postal system had at their disposal about 50000 horses, 1400 oxen, 6700 mules, 4000 carts, and almost 6000 boats.

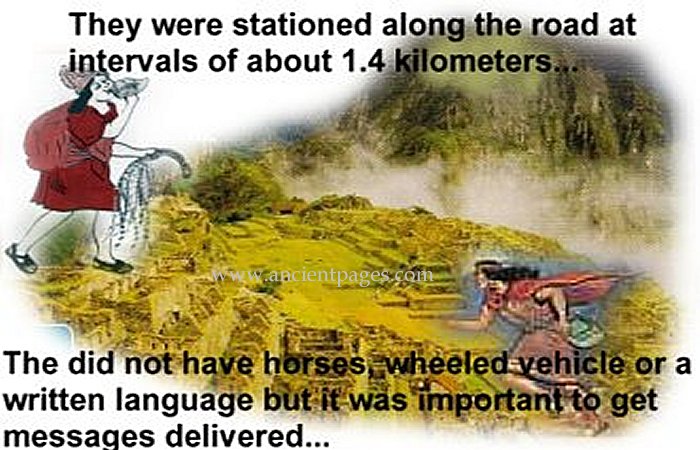

The Inca used couriers, the so called "relay-runners" (chasqui), who were stationed along the road at intervals of approximately 1.4 kilometers.

How did the Inca communicate and how were messages passed across the vast regions of their mountainous country?

How and who did carry messages along mountain-ridge roads, up and then down stone steps, and over precarious chasm-spanning footbridges?

The Inca's system of communicating was adapted to the country's difficult terrain and large distances.

The Inca used couriers, the so called "relay-runners" (chasqui), who were stationed along the road at intervals of approximately 1.4 kilometers. Very speedy running young men from the neighboring communities performed this job as a labor service. They were stationed in pairs at small stone houses along the highway and keeping constant watch for approaching messengers.

Couriers could pass a message from Quito to Cuzco in 10 days, about the same time as it takes today's modern postal service to deliver a letter between those two cities.

The Inca did not have horses, wheeled vehicle or a written language but it was important to get messages delivered.

A message could be relayed verbally or carried on a quipus by couriers and passed from one runner to the next.

All deliveries of messages and goods was done on foot.

The fall of the Roman empire did not immediately destroy the whole postal system in Europe.

Some leftovers of it endured until at least the 9th century but the extensive courier network totally collapsed through most of the middle ages.

Around 1480, kings of Europe had their own heavily armed men responsible for carrying important letters, secret messages and money to different parts of the kingdom's territory.

Ordinary people could only send important messages verbally with travelers and merchants.

Slow but steady resurrection of the courier service started with a help of Maximilian I of Habsburg (1459 – 1519).

This courier service became an extensive, European-wide service by the end of the 17th century.

What was the reason of his great contribution?

Maximillian's purpose was a simple one! He needed to integrate the communications from Austria to the Netherlands, for financial reasons but first of all - military reasons. Northern Italian noble family of Thurn and Taxis supported the extension of this courier service throughout Northern Europe, starting with an integrated postal service serving the European monarchs and extended in the 18th and 19th century and became a publicly available service.

Responsible for postal deliveries, Thurn & Taxis employed 20000 messengers not only to carry mail but also to deliver newspapers. Their vehicles, drawn by four horses, usually four-in-hand, also carried passengers and goods and their postal workers had to conquer ice, snow, and dangerous roads.

Renouard De Valayer, a resident of Paris could, in fact, do a great business with his very first mailbox invented by him in 1653. He invented a short-lived postal system which consisted of mail boxes installed on street corners around Paris.

Seemingly he started a brilliant business but competitors began to do dirty tricks to him. He put mice in his mailboxes and all half eaten letters found in mailboxes, definitely put an end to Valayer's success!

Even in Germany, mail boxes were not particularly popular. A group of Puritan citizens protested against the setting up of mail boxes. They feared that people would keep "secret and immoral correspondence" with each other, if one could get a possibility to send a letter without others' supervision!

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

More From Ancient Pages

-

Hollow Bones That Let Dinosaurs Become Giants Evolved At Least Three Times Independently

News | Apr 11, 2023

Hollow Bones That Let Dinosaurs Become Giants Evolved At Least Three Times Independently

News | Apr 11, 2023 -

Enormous And Impressive Derawar Fort, Bahawalpur, Pakistan Will Be Restored

News | Sep 14, 2015

Enormous And Impressive Derawar Fort, Bahawalpur, Pakistan Will Be Restored

News | Sep 14, 2015 -

Largest And Most Complete Ancient Egyptian Workshops Found In Saqqara

Archaeology | May 28, 2023

Largest And Most Complete Ancient Egyptian Workshops Found In Saqqara

Archaeology | May 28, 2023 -

Ancient People In The Tibetan Plateau Had More Cultural Exchanges Than Previously Thought

Archaeology | Apr 30, 2024

Ancient People In The Tibetan Plateau Had More Cultural Exchanges Than Previously Thought

Archaeology | Apr 30, 2024 -

Namoratunga – Kenya’s Fascinating Megalithic Site Oriented Toward Specific Stars And Constellations

Featured Stories | Jul 6, 2021

Namoratunga – Kenya’s Fascinating Megalithic Site Oriented Toward Specific Stars And Constellations

Featured Stories | Jul 6, 2021 -

Malignant Serpent God Apophis: Symbol Of Chaos And Forces Of Darkness

Ancient Symbols | Oct 13, 2016

Malignant Serpent God Apophis: Symbol Of Chaos And Forces Of Darkness

Ancient Symbols | Oct 13, 2016 -

New Study Challenges The Beginning Of Civilization

Archaeology | Apr 11, 2022

New Study Challenges The Beginning Of Civilization

Archaeology | Apr 11, 2022 -

Unique Ornamented Golden Bronze Age Belt Discovered Near Opava, Czech Republic

Artifacts | Oct 28, 2022

Unique Ornamented Golden Bronze Age Belt Discovered Near Opava, Czech Republic

Artifacts | Oct 28, 2022 -

How Did A Roman Sarcophagus End Up On A Beach Near Varna In Bulgaria?

Archaeology | Aug 6, 2024

How Did A Roman Sarcophagus End Up On A Beach Near Varna In Bulgaria?

Archaeology | Aug 6, 2024 -

Three 3,500-Year-Old Painted Wooden Coffins Discovered In Luxor, Egypt

Archaeology | Dec 3, 2019

Three 3,500-Year-Old Painted Wooden Coffins Discovered In Luxor, Egypt

Archaeology | Dec 3, 2019 -

Mysterious Pyramid-Shaped Tomb Discovered In China

Archaeology | Mar 15, 2017

Mysterious Pyramid-Shaped Tomb Discovered In China

Archaeology | Mar 15, 2017 -

Ancient Egypt Life and Death in the Valley of the Kings Death

Civilizations | Sep 2, 2015

Ancient Egypt Life and Death in the Valley of the Kings Death

Civilizations | Sep 2, 2015 -

Humans’ Evolutionary Relatives Butchered One Another 1.45 Million Years Ago

Ancient Symbols | Jun 26, 2023

Humans’ Evolutionary Relatives Butchered One Another 1.45 Million Years Ago

Ancient Symbols | Jun 26, 2023 -

Fascinating Accounts Of Incredible Vehicles, Cosmic Cities In Vedic Literature

Ancient Mysteries | Oct 6, 2015

Fascinating Accounts Of Incredible Vehicles, Cosmic Cities In Vedic Literature

Ancient Mysteries | Oct 6, 2015 -

Bjorn Ironside: Famous Viking Who Captured Luna By Mistake Instead Of Ancient Rome As Planned

Featured Stories | Jun 11, 2016

Bjorn Ironside: Famous Viking Who Captured Luna By Mistake Instead Of Ancient Rome As Planned

Featured Stories | Jun 11, 2016 -

Next Discovery In Tepe Ashraf, Isfahan – Archaeologists May Have Stumbled Upon Ancient Necropolis

Archaeology | Aug 16, 2020

Next Discovery In Tepe Ashraf, Isfahan – Archaeologists May Have Stumbled Upon Ancient Necropolis

Archaeology | Aug 16, 2020 -

Lares: Roman Household Gods That Protected Home And Family

Ancient Traditions And Customs | Dec 14, 2020

Lares: Roman Household Gods That Protected Home And Family

Ancient Traditions And Customs | Dec 14, 2020 -

A Warrior’s Princely Tomb With Artifacts Unearthed In Romania

Archaeology | Dec 27, 2022

A Warrior’s Princely Tomb With Artifacts Unearthed In Romania

Archaeology | Dec 27, 2022 -

Neanderthals Had Capacity To Speak And Understand Language Like Humans

Archaeology | Mar 2, 2021

Neanderthals Had Capacity To Speak And Understand Language Like Humans

Archaeology | Mar 2, 2021 -

New Details On Discovery Of San Jose 300-Year-Old Shipwreck That Sank With Treasure Of Gold, Silver, And Emeralds

Archaeology | May 23, 2018

New Details On Discovery Of San Jose 300-Year-Old Shipwreck That Sank With Treasure Of Gold, Silver, And Emeralds

Archaeology | May 23, 2018