Edward Of Woodstock “Black Prince” – Idol Of The English People And Terror Of The French

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - Edward of Woodstock (1330-1376) was the eldest son and heir of England's King Edward III Plantagenet.

Historically speaking, he was a very talented leader during the Hundred Years War (1337 to 1453), a series of battles with periods of peace in between, which were fought in France between England and France and later Burgundy.

This statue of Edward The Black Prince by Thomas Brock stands in the City Square In Leeds. Source: Flickr - Chalkstream

Edward (only 16 years old) commanded the English army during the famous Battle of Crecy in 1346.

After his birthplace, he was known as Edward of Woodstock. Interestingly, his nickname "Black Prince" is not mentioned in written historical records until the 16th century, almost two centuries after his death.

Undoubtedly, Edward the Black Prince showed early military genius; he was a talented warrior, motivated and hardened by many years of active presence in battles, which confirmed his excellent martial arts. He was known as a great commander and a thriving tournament participant during his lifetime. His excellent reputation as a chivalric hero also contributed to his fame.

His significant victory over the French at the Battle of Poitiers made him very popular during his lifetime. He captured John the Good, king of France, and Philip the Bold, his youngest son, and did his best to treat them with great respect. He even permitted King John to return home and reportedly prayed with John at Canterbury Cathedral.

The tomb of the Black Prince in the Catedral de Canterbury, 1376. Image credit: Josep Renalias - CC BY-SA 2.5

As R. J. White wrote in his "England: A History," the Black Prince "treated his defeated enemy with the ceremony due to his rank, seating him in his own chair, and serving him food with his own hands…."

Remarkably, this great knight also allowed a day for preparations before the Battle of Poitiers so that the two sides could discuss the coming battle.

Records confirm that contemporaries praised the Black Prince's chivalry, modesty, courage, and even courtesy on the battlefield. However, some claim "he may have been playing for time to complete preparation of his archers' positions."

"The Black Prince was not always a chivalry man, especially regarding his brutalities of war as conducted by him in southern France, where he and his marauding knights behave like freebooters…" (R.J. White)

His main goal was to weaken the unity and economy of France by using medieval warfare to undermine the enemy. He repeatedly ordered the burning, pillaging, and slaughtering of villages and conquered cities. It was against contemporary ideas of chivalry, but it was pretty effective in accomplishing the goals of his campaigns in France.

How did Edward "Black Prince" get this unusual nickname?

Edward The Black Prince receives the grant of Aquitaine from his father King Edward III" Initial letter "E" on a page of illuminated manuscript, date: 1390; British Library. Public Domain

No doubt, Edward was the most famous medieval warrior of his day. But he could be cruel and not always behave as a man of honor. One example can be the city of Limoges, which was stormed and sacked in 1370. Other historians suggested his nickname may have been derived from the French habit of referring to a ruthless commander as a "black boar."

It may originate from his habit when jousting; he used to put aside his royal coat of arms in favor of a "black shield for peace" decorated with three white ostrich feathers.

In her book "Life of Edward the Black Prince," Louise Creighton (1850 – 1936) wrote:

"The sack of Limoges shows us the dark side of chivalry. We must not blame the Black Prince too severely for it. In sacrificing the innocent inhabitants of a whole city for his revenge, he was only acting in accordance with the spirit of the age in which he lived… This was what chivalry led to, and all its bright features cannot make us forgive its disregard of human suffering. Doubtless, this terrible sack is a blot upon the Black Prince's character, but we could hardly have hoped to find him superior to his age…"

"…We must also remember, in his excuse, that he was at that time suffering from a severe and painful illness and suffering even more bitterly in mind at the loss of his proud position and the breakup of his dominions."

But while trying to see what may be said in his excuse, we should not shut our eyes to the seriousness of the crime. The killing of the innocent population could do no good and have no beneficial result.

"…What the Black Prince did was to sacrifice all the inhabitants of a prosperous city to his own thirst for revenge…."

Could these atrocities be in any way explained that he was at that time suffering from a severe and painful illness?"

In 1367, the Black Prince participated in the Spanish campaign, which was unsuccessful. Moreover, he was seriously ill, which forced him to return to England. His critical state of health prevented him from further political activity. He was the first English Prince of Wales who did not become King of England. He died on June 8, 1376, a week before his birthday and one year before his father. He was buried in glory in Canterbury Cathedral.

He was the father of King Richard II of England. He was the first Duke of Cornwall (from 1337), the Prince of Wales (from 1343), and the Prince of Aquitaine (1362–72).

Written by – A. Sutherland AncientPages.com Staff Writer

Updated on November 28, 2022

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesReferences:

Barber, R.. Edward, Prince of Wales and Aquitaine

Creighton L. Life of Edward the Black Prince

White R. J. England: A History

More From Ancient Pages

-

Long-Lost Anglo-Saxon Monastery Ruled By Queen Cynethryth Of Mercia Discovered By Archaeologists

Archaeology | Aug 19, 2021

Long-Lost Anglo-Saxon Monastery Ruled By Queen Cynethryth Of Mercia Discovered By Archaeologists

Archaeology | Aug 19, 2021 -

Ancient Basilica Cistern: Intriguing Hidden Subterranean World With Medusa Heads

Featured Stories | Dec 11, 2018

Ancient Basilica Cistern: Intriguing Hidden Subterranean World With Medusa Heads

Featured Stories | Dec 11, 2018 -

Remarkable Ancient Treasure Found By Man In Ohio Who Refuses To Reveal The Location

Featured Stories | May 2, 2024

Remarkable Ancient Treasure Found By Man In Ohio Who Refuses To Reveal The Location

Featured Stories | May 2, 2024 -

Ouroboros: Ancient Infinity Symbol Used By Different Ancient Civilizations

Ancient Symbols | Oct 3, 2017

Ouroboros: Ancient Infinity Symbol Used By Different Ancient Civilizations

Ancient Symbols | Oct 3, 2017 -

Mystery Of The Copper Age ‘Ivory Lady’ Solved

Archaeology | Jul 6, 2023

Mystery Of The Copper Age ‘Ivory Lady’ Solved

Archaeology | Jul 6, 2023 -

DNA Reveals Stone Age People Avoided Inbreeding

DNA | Mar 9, 2024

DNA Reveals Stone Age People Avoided Inbreeding

DNA | Mar 9, 2024 -

Unique Ancient Map Depicting The Earth As Seen From Space Restored Digitally

Archaeology | Dec 18, 2017

Unique Ancient Map Depicting The Earth As Seen From Space Restored Digitally

Archaeology | Dec 18, 2017 -

Resourceful Neanderthals Could Dive 13ft If Necessary To Collect Shells

Archaeology | Jan 16, 2020

Resourceful Neanderthals Could Dive 13ft If Necessary To Collect Shells

Archaeology | Jan 16, 2020 -

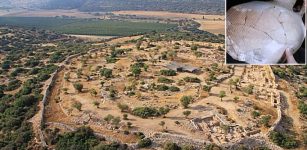

Biblical Tefach: Amazing ‘Common Constant’ Found Among Ancient Storage Jars In Israel

News | Oct 14, 2020

Biblical Tefach: Amazing ‘Common Constant’ Found Among Ancient Storage Jars In Israel

News | Oct 14, 2020 -

Incredible Mammoth Ivory Male Head From Dolni Vestonice, Czech Dated To 26,000 BC

Artifacts | Jun 23, 2015

Incredible Mammoth Ivory Male Head From Dolni Vestonice, Czech Dated To 26,000 BC

Artifacts | Jun 23, 2015 -

Who Built The Mysterious Huapalcalco Pyramid – Mexico’s Smallest Pyramid?

Featured Stories | Mar 29, 2018

Who Built The Mysterious Huapalcalco Pyramid – Mexico’s Smallest Pyramid?

Featured Stories | Mar 29, 2018 -

Amazing 2,000-Year-Old Engraved Roman Gems Discovered Near Hadrian’s Wall

Archaeology | Jan 30, 2023

Amazing 2,000-Year-Old Engraved Roman Gems Discovered Near Hadrian’s Wall

Archaeology | Jan 30, 2023 -

First Record Of Ancient Music Of Babylon

Civilizations | Dec 19, 2014

First Record Of Ancient Music Of Babylon

Civilizations | Dec 19, 2014 -

Mysterious 3,200-Year-Old Hittite Map Of The Cosmos And The 12 Gods

Archaeoastronomy | Jul 2, 2021

Mysterious 3,200-Year-Old Hittite Map Of The Cosmos And The 12 Gods

Archaeoastronomy | Jul 2, 2021 -

Ancient Seal Found In The City Of David: Evidence Of Bethlehem’s Existence Long Before Jesus Was Born

Archaeology | May 24, 2012

Ancient Seal Found In The City Of David: Evidence Of Bethlehem’s Existence Long Before Jesus Was Born

Archaeology | May 24, 2012 -

DNA In Viking Poop Sheds New Light On 55,000-Year-Old Relationship Between Gut Companions

Archaeology | Sep 5, 2022

DNA In Viking Poop Sheds New Light On 55,000-Year-Old Relationship Between Gut Companions

Archaeology | Sep 5, 2022 -

Two Rare Full-Sized Viking Burial Ships Uncovered In Sweden

Archaeology | Jul 5, 2019

Two Rare Full-Sized Viking Burial Ships Uncovered In Sweden

Archaeology | Jul 5, 2019 -

Scientists Argue Over The Mysterious Void Discovered Inside The Great Pyramid Of Giza

Archaeology | Nov 8, 2017

Scientists Argue Over The Mysterious Void Discovered Inside The Great Pyramid Of Giza

Archaeology | Nov 8, 2017 -

Huge Round Ancient Sewer System Covering 160,000 Square Meters Discovered In Ancient City Of Mastaura

Archaeology | Apr 25, 2022

Huge Round Ancient Sewer System Covering 160,000 Square Meters Discovered In Ancient City Of Mastaura

Archaeology | Apr 25, 2022 -

Surprising Mask Of A Human Face Found On Cistern Wall In The Ancient City Of Ptolemais

Archaeology | Jan 17, 2025

Surprising Mask Of A Human Face Found On Cistern Wall In The Ancient City Of Ptolemais

Archaeology | Jan 17, 2025