AncientPages.com - There are hundreds of ancient mounds in coastal Louisiana, USA. Why our ancestors picked certain sites to construct their mounds, has been a subject of debate. What was special about these sites and why were they later abandoned?

Now, scientists think they have solved the mystery and can offer an explanation that shed more light on this ancient puzzle.

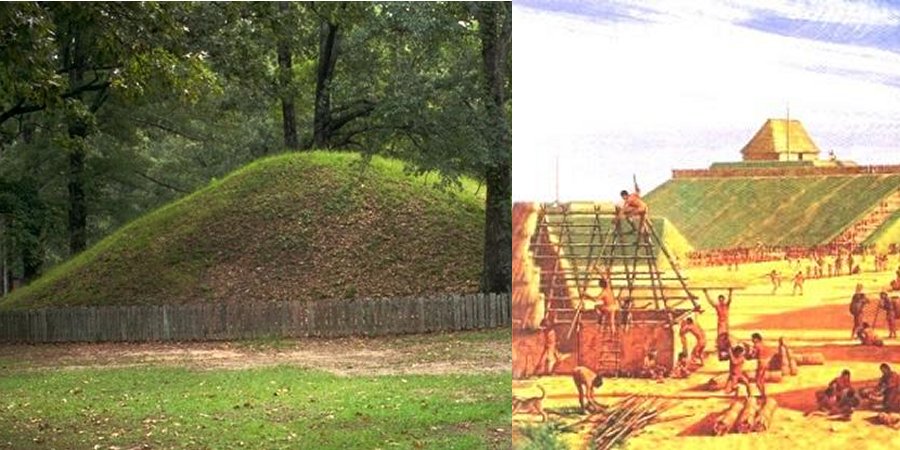

Left: One of the mounds at Marksville State Historic Site. Credit: Louisiana Travel Right: Mound Builders, Credit: Native Indian Tribes

The various cultures collectively termed Mound Builders were inhabitants of North America who, during a 5,000-year period, constructed various types of earthen mounds for religious, ceremonial, burial, and elite residential purposes.

The greatest concentrations of mounds are found in the Mississippi and Ohio valleys. In coastal Louisiana there are still hundreds of ancient mounds in good condition.

Researchers have studied several ancient earthworks on the Mississippi River Delta near present-day New Orleans and say Native Americans knew exactly which places were suitable for their landforms that supported their villages and earthen mounds.

According to anthropology professor Jayur Mehta from the University of Illinois, the site, now known as Grand Caillou, is one of hundreds of mound sites in coastal Louisiana. ""Louisiana is incredibly important in the history of ancient mound-building cultures. In what is now the United States, earthen monument and mound construction began on the Louisiana coast," Mehta explained.

Ancient peoples began building mounds in North America as early as 4,500 B.C., Mehta said. They often situated their mounds near resource-rich waterways, which could support larger human settlements. As many as 500 people lived at Grand Caillou in its heyday. Some mounds also served ceremonial functions.

See also:

World’s Oldest Tattoo Tools Discovered In Tennessee, North America

North America Was Settled By Previously Unknown People – DNA From A 11,500-Year-Old Skeleton Reveals

That so many mound sites have survived in coastal Louisiana is a testament to their careful construction, Mehta said. Neglect, however, and coastal subsidence - the result of engineered changes to the flow of the Mississippi River are wearing away at the mounds.

"Louisiana loses about two ancient mounds and/or Native American villages a year," Mehta said.

To study the mounds, scientists used methods such as sediment coring, radiocarbon dating, and carbon-isotope analysis. This helped them to determine how and when the land underneath the Grand Caillou mound was formed by natural forces and when the mound builders arrived and established their settlement.

The goal was to understand how Indigenous peoples of the coast were choosing where to build their villages.

The result of the study showed that the mound builders set up their village around 1200 A.D., long after the site was stable and covered over with vegetation.

Hundreds of ancient mound sites, depicted here with yellow triangles, still survive in coastal Louisiana. A new study teases out the natural and human history of one of these mound-top villages, a site known as Grand Caillou, shown in red. Credit: Graphic by Julie McMahon after Mehta and Chamberlain.

Core samples and excavations revealed that the mound was built in distinct layers, with clay on the bottom, looser sediments piled in the middle and a clay cap on top. This finding confirms earlier archaeological reports that ancient mounds were engineered in layers to withstand the elements.

"The way they were constructed contributes to their durability," Mehta said.

The Grand Caillou mound was built on top of a river deposit that was naturally higher than surrounding land.

"It's only a few feet higher than nearby areas," Mehta said. "But in a landscape where there's no topography, one or two feet can make a world of difference."

Ceramics found at the site date to between 1000 and 1400 A.D. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal found evidence that the site was abandoned by about 1400. By looking at ratios of carbon isotopes, carbon atoms with differing masses, the team saw changes over time that were likely the result of saltwater incursion into the area. These changes coincided with the ultimate abandonment of the village site.

The study was published in the Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology.

AncientPages.com