Ellen Lloyd - AncientPages.com - One would think twice before committing crimes in ancient Egypt. The punishments for breaking the law were severe and, in some cases, fatal.

Ancient Egyptians had many laws, and those who dared to interfere with the Cosmic Order – Maat had to pay a high price, but not with money. No person stood above the law. No one was special and could be allowed to misbehave.

Maat – Ancient Egypt’s Most Important Religious Concept - read more

Powerful nobles and officials could be punished just as quickly as farmers and pyramid builders.

Depending on the type of crime, a person risked drowning, mutilation, decapitation, or being burned alive.

Maat - The Cosmic Order Must Be Maintained

The Pharaoh was responsible for maintaining the Maat System, and this subject we discussed earlier on Ancient Pages.

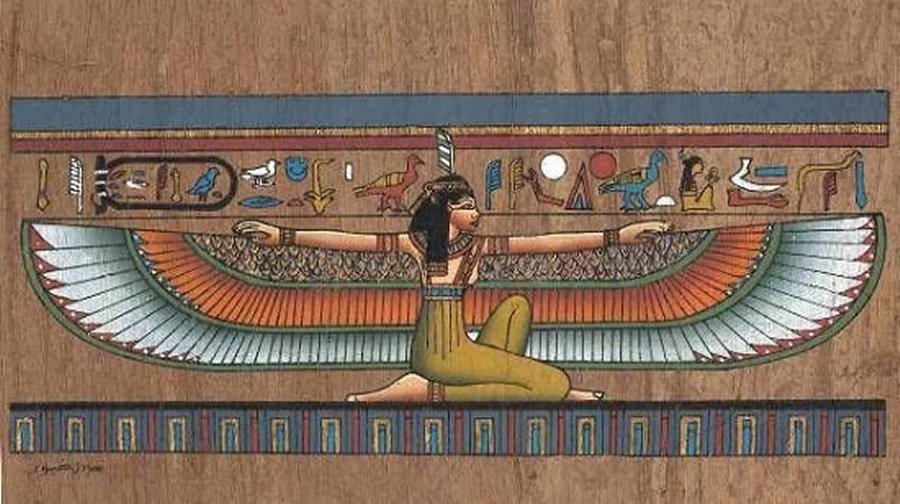

Maat represented the essential religious concept of the Egyptian view of the world. It was a concept of order in the world that the gods, pharaohs, and ordinary people had to obey.

Maat was the Harmony or Law of the Universe. The lack of Maat and her departure meant an inevitable return to the original chaos (Nu) and the end of the known world.

Every Egyptian was responsible for maintaining the Cosmic Order.

The Vizier Was Respected And Feared

Next, after the Pharaoh, the vizier was the most influential person in ancient Egypt. As the highest state official, the vizier was the immediate subordinate of the king, responsible for legal matters, and thus feared by criminals.

The Pharaoh appointed the vizier, and he was usually one of the king's younger brothers. The duties of the vizier were defined in the Instruction of Rekhmire (Installation of the Vizier), a New Kingdom text.

All other lesser supervisors and officials, such as tax collectors and scribes, would report to the vizier. The vizier supervised Pharaoh's security guards and all soldiers who protected temples and palaces.

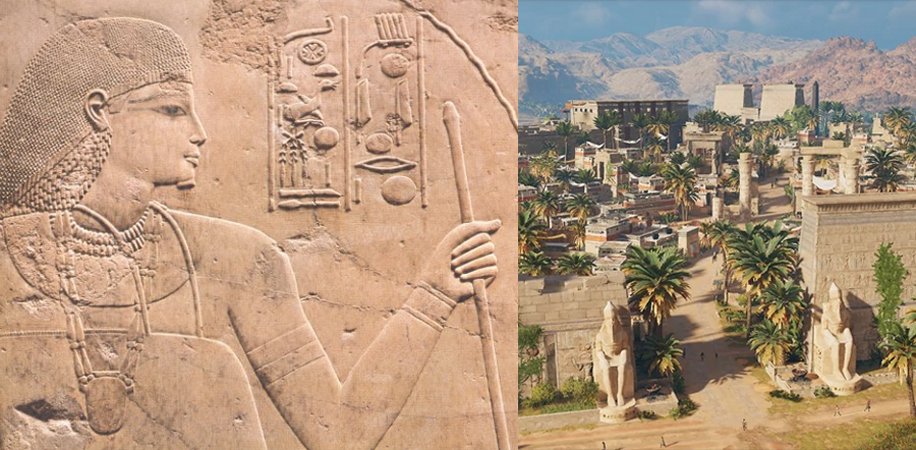

Left: Ramose was the Mayor of Thebes and Vizier of Upper Egypt during the later part of the reign of Amenhotep III and the early part of the reign of Amenhotep IV, who later became Akhenaten. - Credit: donf.com - Right: Artistic impression of Thebes - Credit: XOdeyssusx

The vizier was very powerful and appointed judges. The vizier was the one who defined the punishment for a serious crime. The vizier likely consulted the king concerning all difficult decisions. No one could receive a death sentence in ancient Egypt without the Pharaoh's express permission. The vizier was also not allowed to judge an official based on suspicion and charges without hearing his defense.

The worst prison in ancient Egypt was located in Thebes. Known as the Great Prison, this place served as a confinement and labor camp. In his book Duties of the Vizier, author G. P. F. Van Den Boorn writes, "its inmates included convicted criminals, people awaiting execution for capital crimes and corvée laborers." Statute labor is a corvée imposed by a state for public works. The last-mentioned were unpaid workers.

Ancient Egyptians were highly harsh when they discovered someone had interfered with the Maat system. Anyone who broke the law in Egypt feared the vizier, with good reason.

During the Fifth Dynasty (2,500 B.C. – 2,350 B.C.), Egyptian Vizier Ptahhotep, occasionally known as Ptahhotep I, Ptahhotpe, or Ptah-Hotep, wrote several instructions based on his wisdom and experiences.

His precious text contains advice on how to live your life, and much of what he wrote is still highly relevant today.

The Maxims of Ptahhotep influenced later philosophical works, and his work is one of the first Egyptian books.

Written by Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

Updated on December 1, 2023

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for references