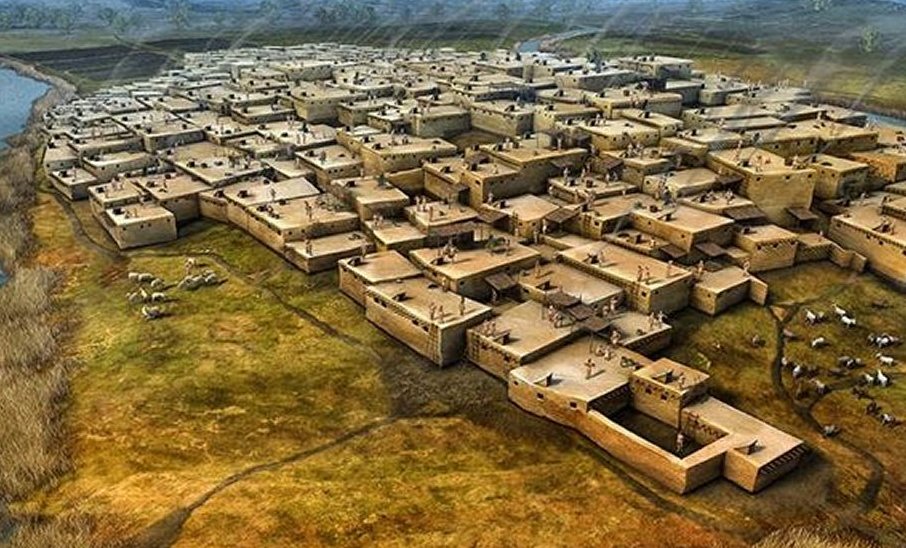

Çatalhöyük – 9,000 Years Ago: Overcrowding, Infectious Diseases, Violence And Environmental Problems Of Early Farmers

Conny Waters - AncientPages.com - Some 9,000 years ago, residents of Çatalhöyük (on modern Turkey,) one of the world's first large farming communities experienced overcrowding, infectious diseases, violence and environmental problems.

Researchers report new findings built on 25 years of study of human remains unearthed at Çatalhöyük, a site, which had 3,500 to 8,000 people at its peak. Çatalhöyük was inhabited from about 7100 to 5950 B.C.

"Çatalhöyük was one of the first proto-urban communities in the world and the residents experienced what happens when you put many people together in a small area for an extended time," Clark Spencer Larsen, lead author of the study, and professor of anthropology at The Ohio State University, said in a press release.

"It set the stage for where we are today and the challenges we face in urban living."

The site measures 13 hectares (about 32 acres) with nearly 21 meters of deposits spanning 1,150 years of continuous occupation. Çatalhöyük (first excavated in 1958)) began as a small settlement about 7100 B.C and later played an important role as a farming community.

"They were farming and keeping animals as soon as they set up the community, but they were intensifying their efforts as the population expanded," Larsen said.

The grain-heavy diet meant that some residents soon developed tooth decay—one of the so-called "diseases of civilization," Larsen said.

Results showed that about 10 to 13 percent of teeth of adults found at the site showed evidence of dental cavities.

"We believe that environmental degradation and climate change forced community members to move further away from the settlement to farm and to find supplies like firewood," he said. "That contributed to the ultimate demise of Çatalhöyük."

See also:

Fascinating Neolithic Society Based On Equality – Catalhoyuk, Turkey

Other research suggests that the climate in the Middle East became drier during the course of Çatalhöyük's history, which made farming more difficult.

Residents suffered from infections (evidence on the bones was found) due to crowding and poor hygiene., which was revealed by analysis of house walls and floors that showed traces of animal and human fecal matter.

Neolithic burial from Çatalhöyük, Turkey, is represented by a headless young adult female with a fetal skeleton (arrow). Skull removal was a burial custom practiced in number of instances at this locality. Credit: the Çatalhöyük Research Project/Jason Quinlan.

Neolithic burial from Çatalhöyük, Turkey, is represented by a headless young adult female with a fetal skeleton (arrow). Skull removal was a burial custom practiced in number of instances at this locality. Credit: the Çatalhöyük Research Project/Jason Quinlan.

"They are living in very crowded conditions, with trash pits and animal pens right next to some of their homes. So there is a whole host of sanitation issues that could contribute to the spread of infectious diseases," Larsen said.

The crowded conditions in Çatalhöyük probably also contributed to high levels of violence between residents.

In a sample of 93 skulls from Çatalhöyük, more than one-fourth—25 individuals—showed evidence of healed fractures. And 12 of them had been victimized more than once, with two to five injuries over a period of time. The shape of the lesions suggested that blows to the head from hard, round objects caused them—and clay balls of the right size and shape were also found at the site.

More than half of the victims were women (13 women, 10 men). And most of the injuries were on the top or back of their heads, suggesting the victims were not facing their assailants when struck.

"We found an increase in cranial injuries during the Middle period, when the population was largest and most dense," Larsen said.

"An argument could be made that overcrowding led to elevated stress and conflict within the community."

Most people were buried in pits that had been dug into the floors of houses, and researchers believe they were interred under the homes in which they lived. That led to an unexpected finding:

Most members of a household were not biologically related.

Written by Conny Waters - AncientPages.com Staff Writer