How Gold Rushes Helped Make The Modern World

AncientPages.com - The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in Coloma, California was one of the most significant events in world history.

On January 24, 1848, while inspecting a mill race for his employer John Sutter, James Marshall glimpsed something glimmering in the cold winter water. “Boys,” he announced, brandishing a nugget to his fellow workers, “I believe I have found a gold mine!”

JCF Johnson’s, Euchre in the bush, circa 1867, depicts a card game in a hut on the Victorian goldfields in the 1860s. Oil on canvas mounted on board, 42.0 x 60.2 cm. Courtesy of the Art Gallery of Ballarat

Marshall had pulled the starting trigger on a global rush that set the world in motion. The impact was sudden – and dramatic. In 1848 California’s non-Indian population was around 14,000; it soared to almost 100,000 by the end of 1849, and to 300,000 by the end of 1853. Some of these people now stare back at us enigmatically through daguerreotypes and tintypes. From Mexico and the Hawaiian Islands; from South and Central America; from Australia and New Zealand; from Southeastern China; from Western and Eastern Europe, arrivals made their way to the golden state.

Looking back later, Mark Twain famously described those who rushed for gold as "a driving, vigorous restless population … an assemblage of two hundred thousand young men – not simpering, dainty, kid-gloved weaklings, but stalwart, muscular, dauntless young braves…"

“The only population of the kind that the world has ever seen gathered together”, Twain reflected, it was “not likely that the world will ever see its like again”.

Arriving at Ballarat in 1895, Twain saw first-hand the incredible economic, political, and social legacies of the Australian gold rushes, which had begun in 1851 and triggered a second global scramble in pursuit of the precious yellow mineral.

See also:

Asenath And The Golden Tablet That Changed Her Destiny

Why Is The Three Golden Balls Symbol For A Pawn Shop Connected To The Medici Family?

Ancient Dacian Gold Helmet With Piercing Evil Eyes

“The smaller discoveries made in the colony of New South Wales three months before,” he observed, “had already started emigrants towards Australia; they had been coming as a stream.” But with the discovery of Victoria’s fabulous gold reserves, which were literally Californian in scale, “they came as a flood”.

Between Sutter’s Mill in January 1848, and the Klondyke (in remote Northwestern Canada) in the late 1890s, the 19th century was regularly subject to such flooding. Across Australasia, Russia, North America, and Southern Africa, 19th century gold discoveries triggered great tidal waves of human, material, and financial movement. New goldfields were inundated by fresh arrivals from around the globe: miners and merchants, bankers and builders, engineers and entrepreneurs, farmers and fossickers, priests and prostitutes, saints and sinners.

A nugget believed to be the first piece of gold discovered in 1848 at Sutter’s Mill in California. Smithsonian National Museum of American History

As the force of the initial wave began to recede, many drifted back to more settled lives in the lands from which they hailed. Others found themselves marooned, and so put down roots in the golden states. Others still, having managed to ride the momentum of the gold wave further inland, toiled on new mineral fields, new farm and pastoral lands, and built settlements, towns and cities. Others again, little attracted to the idea of settling, caught the backwash out across the ocean – and simply kept rushing.

From 1851, for instance, as the golden tide swept towards NSW and Victoria, some 10,000 fortune seekers left North America and bobbed around in the wash to be deposited in Britain’s Antipodean colonies alongside fellow diggers from all over the world.

Gold and global history

The discovery of the precious metal at Sutter’s Mill in January 1848 was a turning point in global history. The rush for gold redirected the technologies of communication and transportation and accelerated and expanded the reach of the American and British Empires.

Telegraph wires, steamships, and railroads followed in their wake; minor ports became major international metropolises for goods and migrants (such as Melbourne and San Francisco) and interior towns and camps became instant cities (think Johannesburg, Denver and Boise). This development was accompanied by accelerated mobility – of goods, people, credit – and anxieties over the erosion of middle class mores around respectability and domesticity.

But gold’s new global connections also brought new forms of destruction and exclusion. The human, economic, and cultural waves that swept through the gold regions could be profoundly destructive to Indigenous and other settled communities, and to the natural environment upon which their material, cultural, and social lives depended. Many of the world’s environments are gold rush landscapes, violently transformed by excavation, piles of tailings, and the reconfiguration of rivers.

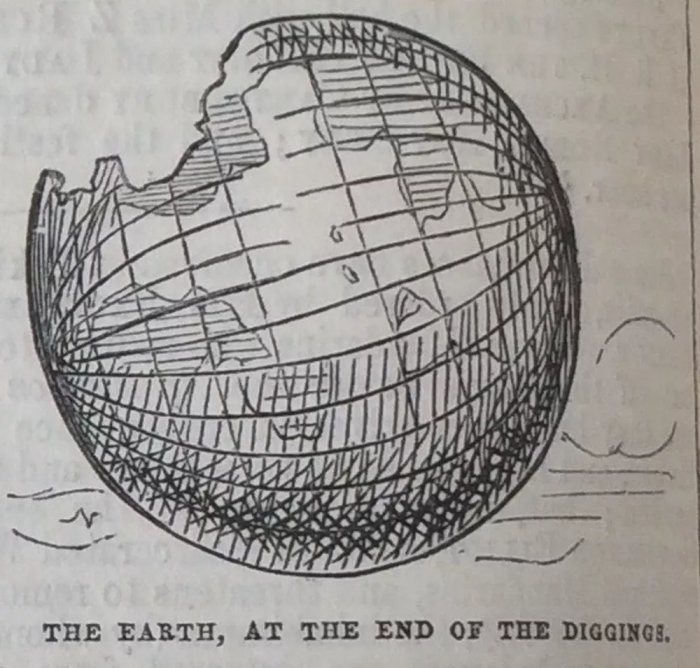

As early as 1849, Punch magazine depicted the spectacle of the earth being hollowed out by gold mining. In the “jaundice regions of California”, the great London journal satirised: “The crust of the earth is already nearly gone … those who wish to pick up the crumbs must proceed at once to California.” As a result, the world appeared to be tipping off its axis.

The Earth, at the End of The Diggings.Courtesy, Ballaarat Mechanics’ Institute.

In the US and beyond, scholars, museum curators, and many family historians have shown us that despite the overwhelmingly male populations of the gold regions, we cannot understand their history as simply “pale and male”. Chinese miners alone constituted more than 25% of the world’s goldseekers, and they now jostle with white miners alongside women, Indigenous and other minority communities in our understanding of the rushes – just as they did on the diggings themselves.

Rushes in the present

The gold rushes are not mere historic footnotes – they continue to influence the world in which we live today. Short-term profits have yielded long-term loss. Gold rush pollution has been just as enduring as the gold rushes’ cultural legacy. Historic pollution has had long-range impacts that environmental agencies and businesses alike continue to grapple with.

At the abandoned Berkley pit mine in Butte, Montana, the water is so saturated with heavy metals that copper can be extracted directly from it. Illegal mining in the Amazon is adding to the pressures on delicate ecosystems and fragile communities struggling to adapt to climate change.

See also:

The Bimaran Casket – Rare Golden Artifact Found In Ancient Stupa

Pyrgi Gold Tablets: A Rare Ancient Bilingual Treasure

Malagana Remarkable Sophisticated Goldwork: Legacy Of Colombian Pre-Hispanic Culture

The phenomenon of rushing is hardly alien to the modern world either - shale gas fracking is an industry of rushes. In the US, the industry has transformed Williston, North Dakota, a city of high rents, ad hoc urban development, and an overwhelmingly young male population – quintessential features of the gold rush city.

In September last year, the Wall Street Journal reported that a new gold rush was under way in Texas: for sand, the vital ingredient in the compound of chemicals and water that is blasted underground to open energy-bearing rock. A rush of community action against fracking’s contamination of groundwater has followed.

The world of the gold rushes, then, is not a distant era of interest only to historians. For better or worse, the rushes are a foundation of many of the patterns of economic, industrial, and environmental change central to our modern-day world of movement.

Written by Benjamin Wilson Mountford - David Myers Research Fellow in History, La Trobe University and Stephen Tuffnell - Associate Professor of Modern US History, University of Oxford

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

More From Ancient Pages

-

Unearthing South Australia’s Oldest Known Shipwreck: The Bark South Australian (1837)

Archaeology | Aug 16, 2023

Unearthing South Australia’s Oldest Known Shipwreck: The Bark South Australian (1837)

Archaeology | Aug 16, 2023 -

Elongated Skulls: Did Intentional And Intriguing Ancient Tradition Originate In China?

Archaeology | Jul 5, 2019

Elongated Skulls: Did Intentional And Intriguing Ancient Tradition Originate In China?

Archaeology | Jul 5, 2019 -

4,000-Year-Old Textile Mill Discovered At Beycesultan Mound In Western Turkey

Archaeology | Sep 25, 2020

4,000-Year-Old Textile Mill Discovered At Beycesultan Mound In Western Turkey

Archaeology | Sep 25, 2020 -

Secret Catacombs With Incredible Ancient Skeletons Covered In Priceless Jewelry

Featured Stories | Nov 20, 2018

Secret Catacombs With Incredible Ancient Skeletons Covered In Priceless Jewelry

Featured Stories | Nov 20, 2018 -

Ancient Secrets Of The Masters Of Mu – Myths And Legends Examined – Part 1

Featured Stories | Aug 24, 2018

Ancient Secrets Of The Masters Of Mu – Myths And Legends Examined – Part 1

Featured Stories | Aug 24, 2018 -

Viking Treasures Discovered In Chamber Grave In Denmark

Archaeology | Apr 4, 2014

Viking Treasures Discovered In Chamber Grave In Denmark

Archaeology | Apr 4, 2014 -

Ancient Burial Of A Princess Who Fell Off A Cliff Raises Many Questions

Archaeology | Apr 18, 2019

Ancient Burial Of A Princess Who Fell Off A Cliff Raises Many Questions

Archaeology | Apr 18, 2019 -

Native Americans Helped Shape The Klamath’s Forests For A Millennia Before European Colonization

Archaeology | Mar 21, 2022

Native Americans Helped Shape The Klamath’s Forests For A Millennia Before European Colonization

Archaeology | Mar 21, 2022 -

Yak Milk Consumption Among Mongol Empire Elites – New Study

Archaeology | Apr 1, 2023

Yak Milk Consumption Among Mongol Empire Elites – New Study

Archaeology | Apr 1, 2023 -

Does Yarmouth Runic Stone Describe A Trans-Atlantic Viking Voyage?

Artifacts | Oct 22, 2018

Does Yarmouth Runic Stone Describe A Trans-Atlantic Viking Voyage?

Artifacts | Oct 22, 2018 -

Mediterranean Sea Was Hotter 2,000 Years Ago And Contributed To The Fall Of The Roman Empire

Archaeology | Jul 27, 2020

Mediterranean Sea Was Hotter 2,000 Years Ago And Contributed To The Fall Of The Roman Empire

Archaeology | Jul 27, 2020 -

Cynane: Talented Female Military Leader Assassinated While Giving A Speech

Featured Stories | Mar 5, 2019

Cynane: Talented Female Military Leader Assassinated While Giving A Speech

Featured Stories | Mar 5, 2019 -

4,000 Years Ago Women Of El Argar Used Their Teeth As Tools

Archaeology | Nov 10, 2020

4,000 Years Ago Women Of El Argar Used Their Teeth As Tools

Archaeology | Nov 10, 2020 -

Ancient Village Of Zalipie Where Flowers Are Painted On All Houses

Ancient Traditions And Customs | May 29, 2019

Ancient Village Of Zalipie Where Flowers Are Painted On All Houses

Ancient Traditions And Customs | May 29, 2019 -

Unusual Stone Carvings And Medieval ‘Witching’ Marks To Ward Off Evil Spirits Discovered In England

Archaeology | Oct 29, 2020

Unusual Stone Carvings And Medieval ‘Witching’ Marks To Ward Off Evil Spirits Discovered In England

Archaeology | Oct 29, 2020 -

Mysterious Nine Worlds Of Yggdrasil – The Sacred Tree Of Life In Norse Mythology

Featured Stories | Mar 8, 2017

Mysterious Nine Worlds Of Yggdrasil – The Sacred Tree Of Life In Norse Mythology

Featured Stories | Mar 8, 2017 -

Solstices Brought Mayan Communities Together, Using Monuments Shaped By Science And Religion – And Kingly Ambitions, Too

Featured Stories | Jul 6, 2024

Solstices Brought Mayan Communities Together, Using Monuments Shaped By Science And Religion – And Kingly Ambitions, Too

Featured Stories | Jul 6, 2024 -

Incamisana Water Temple At Ollantaytambo, Peru: Marvelous Engineering Masterpiece Of Inca

Ancient Technology | Jul 19, 2019

Incamisana Water Temple At Ollantaytambo, Peru: Marvelous Engineering Masterpiece Of Inca

Ancient Technology | Jul 19, 2019 -

Hiding Tunnel Complex Dated To The Bar Kokhba Revolt Revealed Near The Sea of Galilee

Archaeology | Apr 23, 2024

Hiding Tunnel Complex Dated To The Bar Kokhba Revolt Revealed Near The Sea of Galilee

Archaeology | Apr 23, 2024 -

Unexplained Encounters With Unknown Beings In California – Old And Modern Reports

Featured Stories | Mar 11, 2024

Unexplained Encounters With Unknown Beings In California – Old And Modern Reports

Featured Stories | Mar 11, 2024