‘Liber Linteus’ – Unique History Of Ancient ‘Linen Book’ Written In Etruscan That Still Remains Poorly Understood

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - The Etruscan language has never been conclusively shown to be related to any other language in the world. The writing remains poorly understood.

The only known longer text, written in the Etruscan language and dated to around 250 BC, is the "Liber linteus". It has circa 1330 words and represents the longest, single, and well-preserved Etruscan text.

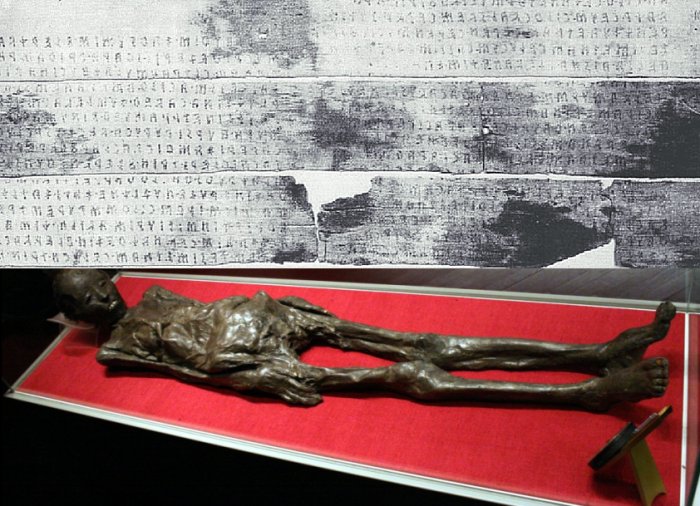

Above: Liber linteus zagrabiensis, the linen book of Zagreb, third-second century BC (© Zagreb Archaeological Museum; Below: Mummy at the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb. Source

"Liber linteus," also known as 'Liber Zagrabiensis' (the 'Linen Book,' 'Book of Zagreb', or even better known as the 'Mummy Wrappings of Zagreb'), has a unique history because of how it was preserved.

The original book had been torn, forming bandage strips subsequently used to bind an Egyptian mummy. It is also the only example of a linen book in the classical world. The significance of this ancient work being written in Etruscan is that very little remains of this mysterious language today.

Originally, Etruscan was widespread over much of the Mediterranean. This can be seen by the thousands of small grave inscriptions and votive gifts dating back to 700 BC and found in Italy, in the Balkans, Africa, Elba, Corsica, Elba, Greece, and the Black Sea.

The language was spoken and written in the Etruscan civilization that existed in Italy at a time before the rise of the Roman Empire.

'Liber linteus' Has A Unique History

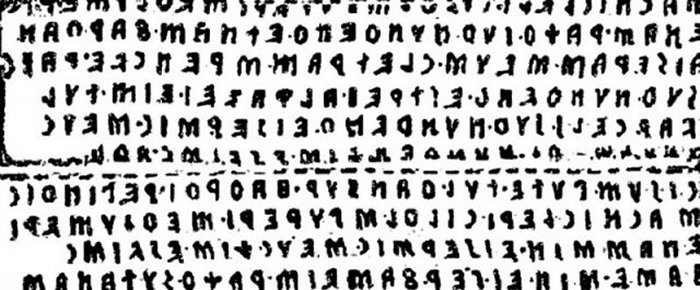

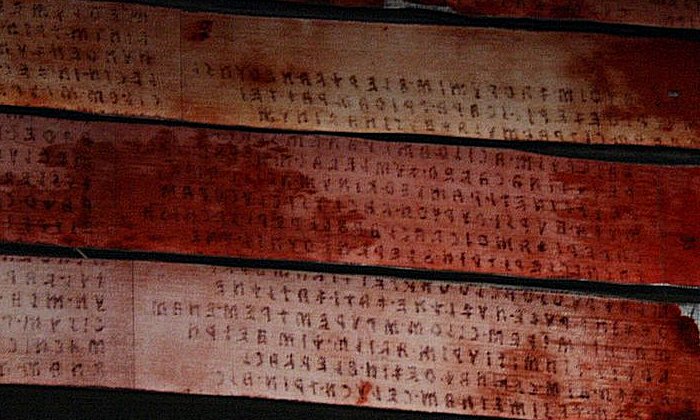

Liber Linteus originally consisted of twelve columns of text written on canvas in black and partly red ink from right to left. At present, most of the first three columns are missing.

Very little remains of this mysterious language today. Source

According to some other interpretations, the text was written by Etruscan priests in one of the temples near Lake Trasimeno, Perugia, Italy, the area originally occupied by the Etruscans. One theory is that the Liber Linteus was written in Egypt in the first century BC for the needs of the Romanized group of Etruscans who settled at that time in North Africa.

The work was not rolled but folded, just like modern books. With the extinction of the Etruscan language, the book lost its practical significance, as it no longer served its original religious purpose.

Priceless Literary Work Cut In Pieces

At some point, the book was cut into narrow strips, several of which served an unknown embalmer as wrappings for a mummified woman's body. In 1848, the mummy was purchased in Alexandria as a souvenir and remained on display in a private home.

Finally, in 1867, the mummy and the manuscript were stored in Zagreb, Croatia, where four years later, it was first realized that the writing was not the Egyptian hieroglyphs. In 1891, Jacob Krall, an expert on the Coptic language. At first, he expected to identify the writing as Coptic (Egyptian written in Greek letters), or an extinct language known as Carian, spoken in Caria, a region of western Anatolia, and related to Lydia and Lycia.

Liber Linteus Zagrebiensis. Image credit: SpeedyGonsales - CC BY 3.0

Krall examined the mummy wrappings and became the first to identify the language as Etruscan. He put the strips back together in the right order, but he could not translate the text.

Genesis Of The Mummy Debated

One theory proposed that the woman was of Etruscan origin and would have left Italy for Egypt due to the uncertain political situation in her country. Many Etruscans fled from Sulla (138 BC—78 BC), a Roman general and statesman, during the Roman-Etruscan Wars. She died in Egypt, and her remains were embalmed and buried.

Later, the mummy was identified as belonging to a young, wealthy Theban woman named Nesi Hensu, the wife of a tailor, Paler Hensu. The woman died during the Ptolemaic reign in Egypt (305 - 30 BC), but how the 'Liber linteus' found the way to Egypt will probably remain a mystery forever.

The question still remains: why was it so easy for Mihajlo Barić (1791–1859), a low-ranking Croatian official, to purchase a sarcophagus containing a female mummy as a souvenir?

One possibility is that the sarcophagus was bought from grave robbers or antique traders in Alexandria.

Today, this rare literary work is in good hands, and undoubtedly, it represents an invaluable treasure for linguists, historians, and archaeologists specializing in the Etruscan language.

Updated on May 26, 2024

Written by – A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesReferences:

Wood, J. R. "The Position of Herbig's 'New Fragment' in the Etruscan Liber Linteus at Zagreb." Glotta 55, no. 3/4 (1977): 283-96.

More From Ancient Pages

-

Nakanishi Ruins: One Of Japan’s Largest Ruins Discovered In Nara

Civilizations | Aug 22, 2015

Nakanishi Ruins: One Of Japan’s Largest Ruins Discovered In Nara

Civilizations | Aug 22, 2015 -

Will Archaeologists Uncover The Secrets Of A Rare Viking Ship Grave In Norway Before It’s Destroyed?

Archaeology | Nov 14, 2020

Will Archaeologists Uncover The Secrets Of A Rare Viking Ship Grave In Norway Before It’s Destroyed?

Archaeology | Nov 14, 2020 -

A Great Flood Destroyed The Mysterious Ancient City Of Petra – Evidence Has Been Found

Archaeology | May 12, 2017

A Great Flood Destroyed The Mysterious Ancient City Of Petra – Evidence Has Been Found

Archaeology | May 12, 2017 -

Thor And Tyr Journey To Hymir’s Hall To Steal Huge Cauldron – In Norse Mythology

Featured Stories | Jun 6, 2023

Thor And Tyr Journey To Hymir’s Hall To Steal Huge Cauldron – In Norse Mythology

Featured Stories | Jun 6, 2023 -

Scientists Solve The Mystery Of Cicero’s Puzzling Words By Analyzing Ancient Roman Coins – Evidence Of Financial Crisis?

Artifacts | Apr 6, 2022

Scientists Solve The Mystery Of Cicero’s Puzzling Words By Analyzing Ancient Roman Coins – Evidence Of Financial Crisis?

Artifacts | Apr 6, 2022 -

Oldest Sea Reptile From Age Of Dinosaurs Found On A Remote Arctic Island

News | Apr 3, 2023

Oldest Sea Reptile From Age Of Dinosaurs Found On A Remote Arctic Island

News | Apr 3, 2023 -

The Magnificent Ancient ‘Flying Airship’ Of King Solomon

Featured Stories | Aug 27, 2018

The Magnificent Ancient ‘Flying Airship’ Of King Solomon

Featured Stories | Aug 27, 2018 -

Ancient Dragon Stone That Inspired Legends Discovered In Turkey

Archaeology | Dec 12, 2018

Ancient Dragon Stone That Inspired Legends Discovered In Turkey

Archaeology | Dec 12, 2018 -

The Untold Story Of Sacsayhuamán – Falcon’s Place Is Not What It Seems

Ancient Mysteries | Apr 28, 2020

The Untold Story Of Sacsayhuamán – Falcon’s Place Is Not What It Seems

Ancient Mysteries | Apr 28, 2020 -

Longest European Burial Mound Pre-Dating The Egyptian Pyramids Discovered In Czechia

Archaeology | Jun 24, 2024

Longest European Burial Mound Pre-Dating The Egyptian Pyramids Discovered In Czechia

Archaeology | Jun 24, 2024 -

Gigantic Karnak Temple Complex: Advanced Ancient Technology In Egypt

Civilizations | Apr 6, 2017

Gigantic Karnak Temple Complex: Advanced Ancient Technology In Egypt

Civilizations | Apr 6, 2017 -

Unearthing Vadnagar And The Search For Hueng Tsang’s 10 Monasteries

Archaeology | Dec 11, 2015

Unearthing Vadnagar And The Search For Hueng Tsang’s 10 Monasteries

Archaeology | Dec 11, 2015 -

Unique Bones Decorated With Black Markings Discovered In 4,500-Year-Old Tomb In Ukraine

Archaeology | Jul 30, 2018

Unique Bones Decorated With Black Markings Discovered In 4,500-Year-Old Tomb In Ukraine

Archaeology | Jul 30, 2018 -

Should Scientists Open An 830-Million-Year-Old Rock Salt Crystal With Ancient Microorganisms That May Still Be Alive?

Archaeology | May 27, 2022

Should Scientists Open An 830-Million-Year-Old Rock Salt Crystal With Ancient Microorganisms That May Still Be Alive?

Archaeology | May 27, 2022 -

Native American Tradition Of A Vision Quest – How To Enter The Spiritual World

Ancient Traditions And Customs | Apr 25, 2017

Native American Tradition Of A Vision Quest – How To Enter The Spiritual World

Ancient Traditions And Customs | Apr 25, 2017 -

Mysterious 4,000-Year-Old Table-Like And Unique Dolmen Discovered In Galilee Hills, Israel

Archaeology | Mar 6, 2017

Mysterious 4,000-Year-Old Table-Like And Unique Dolmen Discovered In Galilee Hills, Israel

Archaeology | Mar 6, 2017 -

Ninkasi – Sumerian Goddess Of Beer And Alcohol – The Hymn To Ninkasi Is An Ancient Recipe For Brewing Beer

Featured Stories | Feb 27, 2019

Ninkasi – Sumerian Goddess Of Beer And Alcohol – The Hymn To Ninkasi Is An Ancient Recipe For Brewing Beer

Featured Stories | Feb 27, 2019 -

Secrets And Lies: Spies Of The Stuart Era Played A Dangerous Game In The Shadows Of An Unstable Europe

Featured Stories | Nov 11, 2024

Secrets And Lies: Spies Of The Stuart Era Played A Dangerous Game In The Shadows Of An Unstable Europe

Featured Stories | Nov 11, 2024 -

The Great Stupa At Sanchi – Oldest Stone Structure In India

Featured Stories | Dec 27, 2015

The Great Stupa At Sanchi – Oldest Stone Structure In India

Featured Stories | Dec 27, 2015 -

This Is The Mysterious Hilltop Where Civilization Began Scientists Say

Archaeology | Jun 24, 2022

This Is The Mysterious Hilltop Where Civilization Began Scientists Say

Archaeology | Jun 24, 2022