Genetic Fingerprints Of Unknown Species Discovered In Human DNA

Conny Waters - AncientPages.com - Scientists have discovered genetic fingerprints of unknown species in human DNA. Lurking within our genome are traces of genetic material from various ancient humans that no longer exist.

These traces reveal a long intermingling history, as our direct ancestors encountered and mated with archaic humans.

For most of our evolutionary history - for most of the time anatomically modern humans have been on Earth- we've shared the planet with other species of humans.

In the last 30,000 years, the mere blink of an evolutionary eye, modern humans have occupied the planet as the sole representative of the hominin lineage.

Genetic Archaeology Can Answer Who Humans Descended From

The clues to human beginnings are hidden in DNA, and scientists keep discovering surprises that give reason to rewrite our ancient history.

The study of DNA is essential to learn more about how humans evolved. Credit: Public Domain

Joshua Akey, a Professor in the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics specializes in what he calls genetic archaeology, a method that he thinks offers information not only about extinct humans but also about the larger picture of how we evolved as a species.

"We can excavate different types of humans not from dirt and fossils but directly from DNA," he said.

Combining his expertise in biology and Darwinian evolution with computational and statistical methods, Professor Akey studied the genetic connections between modern humans and two species of extinct hominins: Neanderthals, the classical "cave men" of paleoanthropology; and Denisovans, a recently discovered archaic human.

Like many of us, Akey has long been interested in how the human species evolved. "People want to learn about their past," he said.

"But even more than that, we want to know what it means to be human."

For many years scientists wondered whether modern humans carried genes from Neanderthals, and today we do know that there had been gene flow from Neanderthals to modern humans.

Researchers estimate that people of non-African ancestry had about 2% Neanderthal ancestry.

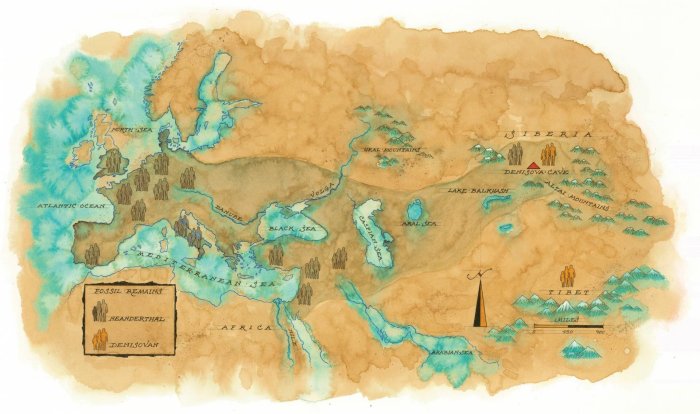

Neanderthals lived in a wide geographical swath across Europe, the Near East and Central Asia before dying out around 30,000 years ago. They lived alongside anatomically modern humans, who evolved in Africa some 200,000 years ago.

The archaeological record shows that Neanderthals were adept at making stone tools and developed several physical traits that uniquely adapted them to cold, dark climates, such as broad noses, thick body hair, and large eyes.

Genetic Fingerprints Of Unknown Species Has Been Found In Human DNA

Using his method, Professor Akey has uncovered a rich human legacy of genetic interconnections on a previously unconceived scale.

As stated, while the available evidence suggests that non-Africans carry about 2% of Neanderthal genes, Africans, who were once believed not to have any connections with Neanderthals, actually have approximately 0.5% Neanderthal genes.

Neanderthals are our closest extinct relatives and modern humans share 99.7% of their DNA. Credit: Public Domain

Researchers have further discovered that the Neanderthal genome has contributed to several diseases seen in modern human populations, such as diabetes, arthritis and celiac disease. By the same token, some genes inherited from Neanderthals have proven beneficial or neutral, such as genes for hair and skin color, sleep patterns and even mood.

Akey has also discovered genetic fingerprints that suggest our human ancestry contains species about which we know nothing or very little. The Denisovans are a case in point.

An archaic form of humans, they coexisted with anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals and interbred with both before going extinct.

The first evidence of their existence came in 2008 when a finger bone was discovered in Denisova Cave in the remote Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. At first, the bone was assumed to be Neanderthal because the cave contained evidence of these species. Consequently, it sat in a museum drawer in Leipzig, Germany, for many years before it was analyzed.

But when it was, the researchers were dumbfounded. It wasn't a Neanderthal—it was a hitherto unknown type of ancient human.

"The Denisovans are the first species ever identified directly from their DNA and not from fossil data," Akey said.

A Connection Between The Denisovans And Modern Melanesians

Since that time, continued genetic work—much of it conducted by Akey and his colleagues—has established that the closest living relatives of Denisovans are modern Melanesians, the inhabitants of the Melanesian islands of the western Pacific—places such as New Guinea, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and Fiji. These populations carry between 4% and 6% of Denisovan genes, though they also carry Neanderthal genes.

Joshua Akey, a professor in the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, uses a research method he calls genetic archaeology to transform how we’re learning about our past. Fossil evidence illustrates the spread of two long-extinct hominin species, Neanderthals and Denisovans. Modern humans carry genes from these species, indicating that our direct ancestors encountered and mated with archaic humans. Credit: Michael Francis Reagan

Examples like this highlight one of the main features of our human lineage, Akey said, that admixture has been a defining feature of our history.

"Throughout human history there's always been admixture," Akey said. "Populations split and they come back together."

While there remains a lot of debate about the Denisovans, Akey believes they most likely were closely related to Neanderthals, perhaps an eastern version who split off from the latter sometime around 300,000 or 400,000 years ago.

Recently, genetic analysis of fossils from Denisova Cave has uncovered evidence of an offspring between a Neanderthal woman and a Denisovan male. The offspring was a female who lived approximately 90,000 years ago.

See also: More Archaeology News

By looking at this genetic trail, Akey and other researchers have been able to piece together a fascinating story of human evolution that promises to rewrite our understanding of early human origins.

But there's so much more to discover, Akey said. "Even though we have sequenced probably 100,000 genomes already, and we have pretty sophisticated tools for looking at that variation, the more we think about how to interpret genetic variation, the more we find these hidden stories in our DNA," he said.

Written by Conny Waters - AncientPages.com Staff Writer