Ancient Egyptian Blue Used To Create New Nanomaterial 100,000 Times Thinner Than A Human Hair

Jan Bartek – AncientPages.com – The Egyptian blue is the world’s oldest artificial pigment. It has extraordinary properties that allow scientists to reconstruct the past and shape the technology of the future.

To ancient Egyptians, blue was a very important color that was associated with the sky and the river Nile and thus came to represent the universe, creation, and fertility.

Egyptian blue was widely used in ancient times as a pigment in paintings, such as in wall paintings, tombs, mummies’ coffins, and a ceramic glaze known as Egyptian faience. The fact that it was not available naturally meant that its presence indicated a work that had considerable prestige. Its use spread throughout Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and the far reaches of the Roman Empire. It was often used as a substitute for lapis lazuli, an extremely expensive and rare mineral sourced in Afghanistan.

It's important to remember that Egyptian blue is much more than just a color that adorns, for instance, the crown of the world-famous bust of Nefertiti.

Modern scientists have noticed that when irradiated with visible light, Egyptian blue emits near-infrared rays with exceptional strength, with even single particles of the pigment detectable from a distance of a few yards.

This suggests Egyptian blue could have a variety of modern applications. For example, it could soon be used in advanced biomedical engineering. Expanding on the ancient Egyptian concept of the pigment's near-infrared-emitting property, scientists can also use it as a nano-ink.

Ancient Egyptian blue powder can make fingerprints glow and will be used by crime scene investigators.

Scientists from the Institute of Physical Chemistry at the University of Göttingen have produced a new nanomaterial based on the Egyptian blue pigment, which is ideally suited for applications in imaging using near-infrared spectroscopy and microscopy.

Microscopy and optical imaging are important tools in basic research and biomedicine. They use substances that can release light when excited. Known as “fluorophores,” these substances are used to stain very small structures in samples, enabling clear resolution using modern microscopes. Most fluorophores shine in the range of light visible to humans.

When using light in the near-infrared spectrum, with a wavelength starting at 800 nanometres, light penetrates even deeper into the tissue, and the image has fewer distortions. So far, however, only a few known fluorophores work in the near-infrared spectrum.

The research team has now succeeded in exfoliating extremely thin layers from grains of calcium copper silicate, also known as Egyptian blue. These nanosheets are 100,000 times thinner than human hair and fluoresce in the near-infrared range. "We were able to show that even the smallest nanosheets are extremely stable, shine brightly, and do not bleach," says Dr. Sebastian Kruss, "making them ideal for optical imaging.“

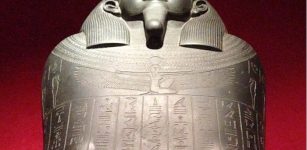

Pyxis made out of "Egyptian blue": Imported to Italy from northern Syria, it was produced 750-700 BC. Credit: Bairuilong, CC BY-SA 4.0

The scientists tested their idea for microscopy in animals and plants. For example, they followed the movement of individual nanosheets in order to visualize mechanical processes and the structure of the tissue around cell nuclei in the fruit fly. In addition, they integrated the nanosheets into plants and were able to identify them even without a microscope, which promises future applications in the agricultural industry.

"The potential for state-of-the-art microscopy from this material means that new findings in biomedical research can be expected in the future," says Kruss.

The Egyptian blue has once again confirmed it's more than just a color.

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer