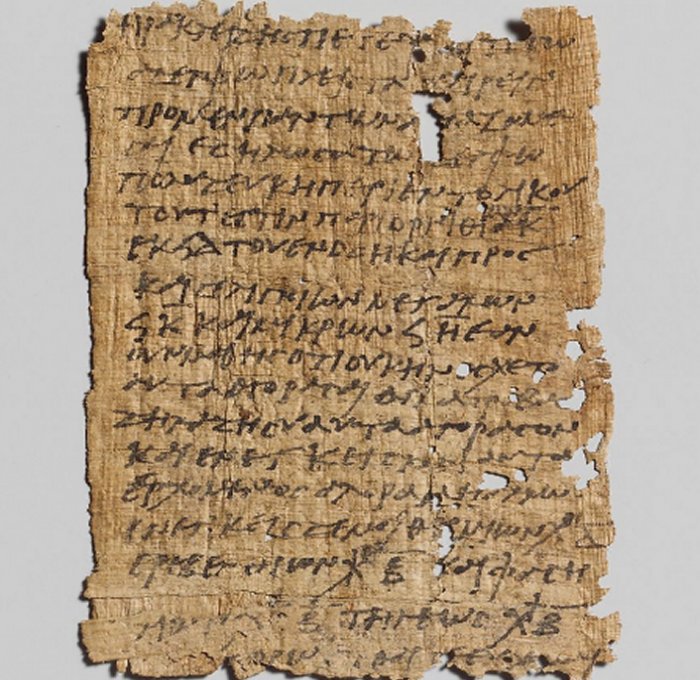

Conny Waters - AncientPages.com - Until the 9th century, 200 years after the Arabs took power in Egypt, papyrus scrolls, known from the beginning of the pharaonic state, were used for daily records and administration.

In 642, the Arab commander Amr Ibn al-As and his troops conquered all of Egypt, taking it from the rulers of the Byzantine Empire. At that time, Christianity was the dominant religion in Egypt. But its followers were divided into two larger groups: the Melkite church subordinated to the patriarchs in Constantinople and the second, more local, native Coptic church.

“The Copts felt persecuted by the Melkite clergy in the 7th century despite the fact that Christianity was the dominant religion," papyrologist Tomasz Barański from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology at the University of Warsaw and a specialist in early Arabic texts from Egypt told Science in Poland.

"They sometimes referred to the arrival of Arab troops as liberation from Byzantine power. In any case, these conclusions can be drawn from somewhat later texts.”

The Arab invasion was not very bloody compared to other ancient wars and conflicts, but the inhabitants of Egypt could still remember the Persian invasion of 619, which was definitely more difficult for the inhabitants due to looting and damage. Meanwhile, in the case of the Arab invasion, in the first decades, changes occurred mainly at the height of power, showing that there was no revolution that papyruses, used in Egypt for many thousands of years, continued to be used for the administration of the country.

Papyrus is a writing material made from cut stems of papyrus plant growing over the Nile in antiquity and the Middle Ages. Today, however, this plant does not grow naturally in Egypt. The papyrus records contained tax collection orders and receipts, marriages, sales contracts, as well as official and private letters. Individual cards were cut from long papyrus scrolls. Papyri were replaced only about 200 years after the Arab invasion of Egypt, at the turn of the 9th century, when paper quickly began to gain popularity, the researcher explains.

Although the Arab takeover took place quite quickly, it was not associated with a rapid flood of incomers from the Arabian Peninsula.

Barański said: “Even 100 years after the political subordination of Egypt, the invaders were a clear minority, it was probably tens of thousands of people, a drop in the population of several million country.”

From the mid-8th century, relocations of the Arab population, primarily to the Nile Delta are known from historical sources.

“The current population of Egypt is very strongly genetically mixed. Immigration took place from various directions, also from the south, from Nubia. But in later periods, for example in the Mamluk period, there was a large influx of Caucasian and Turkish immigrants. This does not change the fact that, to a large extent, the population of Egypt is genetically strongly associated with the population living there since antiquity,” he said.

The process of adopting Arab identity by local residents progressed gradually from the turn of the 8th century, several decades after the conquest. Such observations are possible based on documents from this period.

Barański said: “Sons have Muslim, typically Arabic names, and their fathers still have Christian or even ancient Egyptian names. Such documents are evidence of a religious and social transformation.”

The Egyptians were eager to accept an Arab identity, which was associated with many potential benefits: the closer to power, the more accessible lucrative jobs were. Interestingly, Arabisation progressed much faster than Islamisation. According to Barański, it was not until ca. 12th century that half of the population was Muslim. But the vast majority adopted the Arabic language and in part also Arabic identity earlier.

The study shows that the changes under the influence of the Arab conquest occurred more slowly than previously believed. One of the papyri contains a receipt for part of the tax for a given year from an administrative district in central Egypt. The document was written in Arabic and Greek. Greek was still used in Egyptian administration in the 8th century, and Coptic even in the 9th century. The latter was an ancient Egyptian language written with characters taken from the Greek language, it was still used in writing in the 11th century.

Until now the bilingual document examined by Barański was thought to be from the 7th century. But the researcher noticed that the date had been previously misread. It turned out that the document was made a few decades later, in the 8th century.

“Meanwhile, this document was considered evidence of a rapid Arabisation of the low-level Egyptian administration. It seems, however, that it happened a little later,” the researcher added.

While reading documents from early Muslim Egypt, Barański also finds evidence of human tragedies. Among them, a tax payment receipt for a woman.

He said: “In principle, poll tax had to be paid only by men. It seems that the head of the family left the family home to avoid this obligation. As a consequence, the woman was forced to fulfill this obligation herself on behalf of her family.”

Written by Conny Waters - AncientPages.com Staff Writer