Underwater Artifacts Shed New Light On Battle Of The Egadi Islands Between Romans And Carthage

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - On March 10, 241 B.C. the Carthaginian fleet was totally defeated near the Aegates Islands off western Sicily by the Romans. The event known as the Battle of the Egadi Islands was the final battle of the First Punic War.

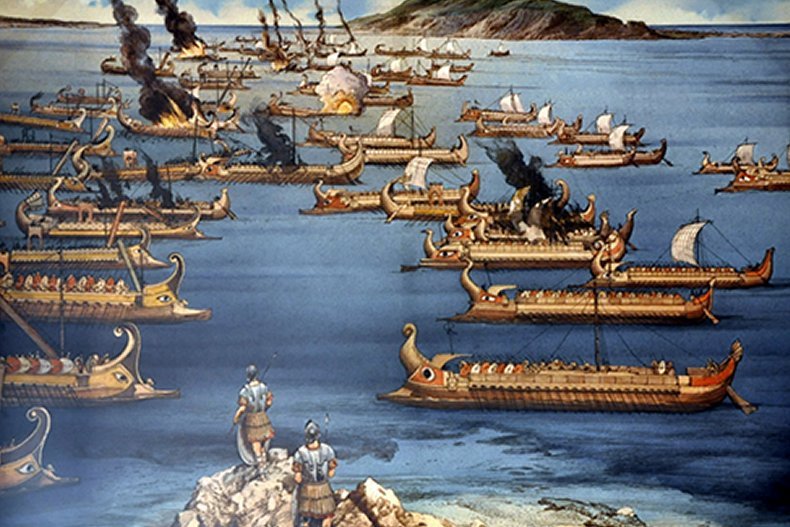

On March 10 241BC a huge naval battle took place off the coast of Sicily between the Romans and their archenemies the Carthaginians. It put an end to the First Punic War and set the Roman Republic on its militaristic path to becoming an Empire. Photo: RPMNF projects

Carthage had ruled much of the Mediterranean through mercenary armies for about 600 years. Founded in the 9th century BC by the Phoenicians, Carthage had grown into a large influential empire. In 264 B.C. Carthage and Rome went to war, starting the First Punic War. The immediate cause of the war was the issue of control of the independent Sicilian city-state of Messana (modern Messina). This was the beginning of a long conflict that resulted in three Punic Wars between Romans and Carthage that lasted almost 100 years.

Bronze ram of a ship being raised from the sea floor. Credit: Superintendenza del Mare

The Battle of the Egadi Islands was a decisive moment in history because the battle produced a victory for Rome that established the Romans as a major Mediterranean power.

There are many history books about the Punic Wars and the struggles between Carthage and Romans, but one of the best ways to gain information about these historical events is to explore the ships and artifacts that are submerged.

RPM Nautical Foundation under the guidance of the late Sebastiano Tusa and the Sicilian Superintendency of the Sea has investigated the underwater sites where the battles took place and they have found many ancient treasures.

Credit: RPM Nautical Foundation

So far the team “has located a number of bronze rams, heavy metal warheads from the bows of ancient oared warships. Rams are the rarest of naval finds with only seven recovered prior to the Egadi discoveries. By 2019, the team had identified 23 warheads from this battle.

In addition to these rare finds, they have also found scores of bronze helmets, Carthaginian coins, and close to 900 clay containers, called amphoras, that held supplies intended for a Carthaginian garrison on Western Sicily. Surprisingly, swords from this period of Roman history are extremely rare and the team, now augmented by divers, is starting to locate these as well,” University of Florida reports.

Punic inscription on ship’s ram. Credit: Emma Salvo

Mapping every submerged ancient object by GPS coordinates allows scientists to produce a detailed map of the debris field. William Murray, Professor of Ancient History at the University of South Florida, has “long tried to hypothesize the surface positions of the warships at the moment they were destroyed, when they released their clay jars, swords, knives, helmets, coins and panicked men into the water.

Since the battle zone is swept by strong currents, the team needed to know how far the items dropped from the surface might have traveled before they hit the bottom. Armed with a Creative Scholarship Grant from USF’s Research Council, Murray carried out a series of experiments in 2019 to answer some of these questions.

Using six replica storage jars made to order by a local potter and three replica helmets made for ancient war game reenactors, Murray and his team conducted a series of controlled drops in a region of the battle zone where the water is almost 300 feet deep. Unsurprisingly, the helmets and amphoras that were filled with liquids (wine and oil) sank quickly to the bottom, traveling between 16 and 33 meters from their release points. But amphoras filled with wheat, known to be carried by the fleet, floated for up to an hour before sinking and traveling roughly a kilometer down current from where they were released.

Montefortino helmets found off the Egadi Islands. Credit: Emma Salvo

When these results were compared with a GIS (geographic information system) map of the debris field, the situation clarified. Suddenly, Murray could see the positions of the warships when the two fleets collided.

It seems now that many ships went to the bottom quickly, just as our best accounts reported the action, but they left behind more than a thousand amphoras that bobbed with the current for up to an hour and produced the spread-out pattern of clay jars we see today.”

See also: More Archaeology News

On the last few days of the survey, the team tested their new theory by searching for warship rams in an area to the northeast of a scatter of jars, and to their delight they found four additional rams. Armed with this new understanding of the battle zone, Murray and his fellow researchers can hardly wait until an effective COVID-19 vaccine allows the US-based team to continue their search to define the battle zone with their Sicilian colleagues.

The results of this research are featured in a series of nine lectures streamed to various locations around the country by Murray, as this year's distinguished Martha Sharp Joukowsky Lecturer for the Archaeological Institute of America.

It will most likely be enjoyable to watch if you are interested in ancient Roman history or naval battles in general.

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer