Ellen Lloyd - AncientPages.com - Johann Gutenberg’s brilliant printing press changed Europe’s history. People were excited when the first printed books started appearing in Europe. Thousands of titles were now available, and more and more people could buy previously rare and expensive books.

However, though Gutenberg’s printed press was appreciated by most, some considered the mass distribution of printed books dangerous. Several scholars were against the printing press. So, why did the first printed books scare scholars in Europe?

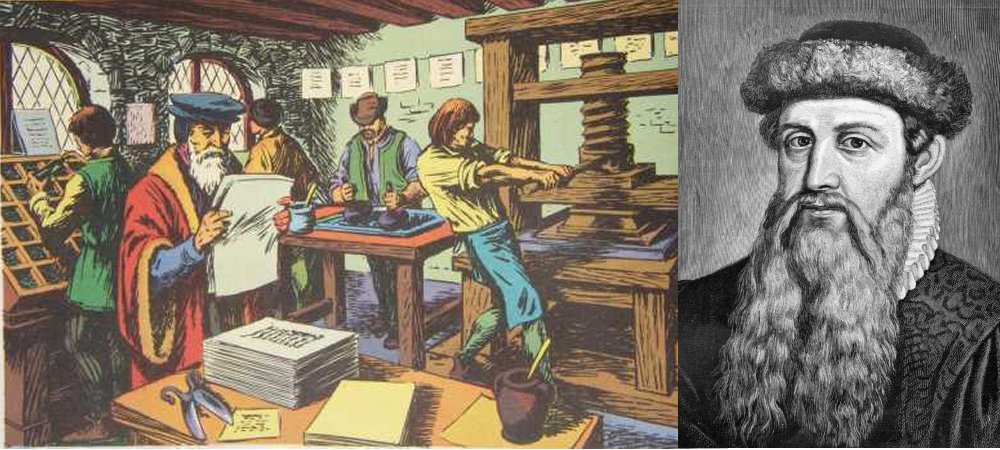

Left: Gutenberg's printing press was appreciated by many, but far from all. Right: Johannes Gutenberg (1400-1468), Public Domain

We should not forget that Johannes Gutenberg did not invent the printing press. He contributed to movable type mechanical printing technology in Europe in 1450. Chinese and Korean inventors produced printed books for centuries before Gutenberg was born. The world’s first known movable type printing was a Chinese invention.

Gutenberg adapted the technology for a Western market and turned it into a publishing empire.

On February 23, 1455, Europe’s first mass-produced book – the Gutenberg Bible – was printed with movable type in Mainz, Germany. The book was a Latin language Bible.

Gutenberg’s printing press helped to popularize books and the information they contained.

His invention revolutionized the distribution of knowledge by producing many accurate copies of a single work.

Scholars Believed That Too Much Knowledge Was Dangerous To Ordinary People

To many scholars, the easy distribution of knowledge was a problem. One scholar who spoke against Gutenberg’s printing press was Conrad Gessner (1516-1565), a Swiss physician, naturalist, bibliographer, and philologist.

Gessner was, in many ways, an outstanding scholar and wrote several books, but he certainly didn’t like the printing press. Gessner created a list of all books published with the help of Gutenberg’s printing press over 100 years, and it contained as many as 10,000 titles accessible to readers in Europe.

According to Gessner, this was shocking, absurd, and dangerous. Gessner’s argument against the printing press was that ordinary people could not handle so much knowledge.

William Caxton shows his printing press to King Edward IV. Credit: Prepressure

Gessner demanded that those in power in European countries enforce a law regulating the sales and distribution of books. He felt ordinary people should not have access to such many books. Gessner was not a person who hated books. On the contrary, according to a legend, he wished to spend his last day in a library, a place he loved, and at the time of his death, he had published 72 books and written 18 more unpublished manuscripts.

Gessner was not the only one who was annoyed with the printing press. Several scholars shared his views. One of them was Adrien Baillet (1649 – 1706), a French scholar and critic who is best known for his biography of Descartes. Baillet believed that all views presented in books would divide Europe. In a work entitled "Jugemens des savants sur les principaux ouvrages des auteurs", Baillet wrote: “We have reason to fear that the multitude of books that is increasing every day in a prodigious manner will put the centuries to come into as difficult a state as that in which barbarity had put the earlier ones after the fall of the Roman Empire."

Gutenberg’s Printing Press Left Monks Unemployed

Prior to the invention of printing, press books were produced by hand. Large monasteries had rooms called scriptoria, where monks would copy manuscripts. The process of producing a book was time-consuming. For example, the Bible was copied by hand, and it would take a single monk 20 years to transcribe it.

Prior to Gutenberg's printing press monks were responsible for writing. Credit: Walking in the Desert

German Benedictine abbot Johannes Trithemius (1462 – 1516) was very concerned that thousands of monks responsible for writing would be left with nothing to do. In his work In Praise of Scribes, Trithemius wrote: “If writing is inscribed on parchment, it will last a millennium. But if it is on paper, how long will it last? Two hundred years would be a lot." He urged the scribes to “perpetuate in writing the useful products of the press.”

Interestingly, Trithemius had nothing against that his writings were published with the help of Gutenberg’s printing press.

To many scholars and theologians, Gutenberg’s printing press was a threat. It was said books would divide Europe, create chaos, harm peoples' knowledge, and monks would be without work.

For all of us who love books, it’s a good thing the printing press survived despite the fierce opposition.

Updated on October 24, 2023

Written by - Ellen Lloyd – AncientPages.com

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com