Garamantes: 3,000-Year-Old Sophisticated North African Society Built 3,000-Mile Network Of Underground Irrigation Canals

A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com - Many legends surround the mysterious Kingdom of Garamantes, which was once situated in the oases of Fezzan, Libya.

This indigenous Saharan society had towns, flourishing oasis agriculture, technological achievements, and trading contacts with the Mediterranean and Sub-Saharan Africa. During the Neolithic period in Africa (ca 1000 BC) and until about the time of the Arab Conquest, dated to the 7th century AD, the Garamantes developed a sophisticated society with the fortified capital city Garama and other cities.

Left: Ancient Libyan, possibly Garamante, depicted in the tomb of Pharaoh Seti I. Image credit: Unknown (original) Heinrich Menu von Minutoli (1772–1846) (drawing) – Public Domain: Right: Ruins of Garama, the central city of the Garamantes. Image credit: Franzfoto - CC BY-SA 3.0

Politically organized in confederation, the Garamantes were governed by a king. The Garamantes were not desert barbarians living in one or two small towns and some settlements scattered across the vast realm of the Sahara Desert.

It was undoubtedly erroneous if someone had such an opinion about the Garamantes people.

We must not forget that this extraordinary, advanced society lived surrounded by the Sahara Desert, the world's largest desert, where rainfall averages only half an inch yearly.

Yet, the Garamantes flourished, and so did their agriculture.

The Garamantes were cattle and horse breeders, charioteers, and light horses. They were skilled builders who possessed knowledge of architecture. This resourceful society built a 3,000-mile network of underground irrigation canals, which tapped into natural fossil water supplies laid down more than 40,000 years ago when rain last fell plentifully in the area.

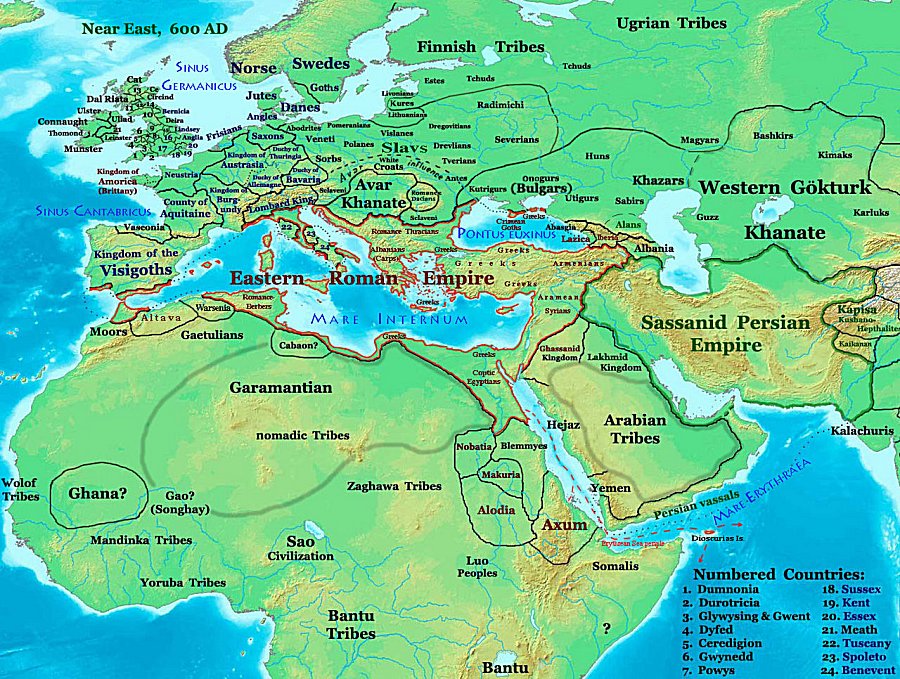

Location of the Garamantes in the Fezzan 600 AD, before the Islamic conquest. Image credit: Talessman - CC BY-SA 3.0

Location of the Garamantes in the Fezzan 600 AD, before the Islamic conquest. Image credit: Talessman - CC BY-SA 3.0

They practiced oasis agriculture; they were farmers and merchants whose diet included grapes, figs, wheat, and barley. They traded Rome's wheat, salt, imported olive oil, oil lamps, and tableware.

According to Strabo and Pliny sources, the Garamantes mined amazonite in the Tibesti Mountains of the central Sahara. However, the analysis of their skeletons revealed that these people were healthy and not subjected to exhausting activities or regular warfare.

Their kingdom included eight or more major towns and many other settlements, considered as old as 3,000 years. As the 1960s excavations revealed, the Garamantes' capital Garama (modern Germa), had approximately four thousand inhabitants, and another six thousand lived in villages within a 5 km radius.

The peak of their prosperity is dated between 500 and ca 600 AD, before the Islamic Conquest.

The Garamantes successfully exploited fossil water sources to irrigate crops by practicing oasis agriculture. Their extraordinary society included many skilled artisans and manufacturers devoted to metalworking and textile production. Traces of these activities were unearthed at the archaeological sites.

Aerial view of the ancient site of Garama. Image credit: Katy Tzaralunga – CC BY 2.0

They also left in legacy the abundant rock art, which often depicts life, before the rise of their kingdom.

Much of what we know of this civilization has originated from contemporary Greek and Roman foreign accounts and modern archaeological findings.

According to the Greek historian Herodotus, the Garamantes were a "very great nation." Roman descriptions describe them as wearing scarifications and tattoos. Tacitus, a Roman historian and politician, wrote that they aided Tacfarinas, a former Roman soldier, during his rebellion between 17 and 24 AD and raided Greco - Roman coastal cities.

Ancient Garamante script. Image credit: Think Africa. Image source.

Significant research conducted by Professor David Mattingly of the University of Leicester's School of Archaeology and Ancient History and his team opened our eyes to the lost civilization of the Garamantes people.

The discoveries revealed that the sun-beaten and arid lands of the Sahara have been much more crowded than previously thought. Around 150 AD, the Garamantes kingdom, located mainly along the Wadi al-Ajal, occupied an area that covered 180,000 square kilometers in southern Libya.

Using aerial photography and satellite imagery, Professor Mattingly and his team have pieced together the area's archaeological heritage and discovered hundreds of fortified oasis settlements and advanced water and irrigation systems that sustained advanced oasis agriculture.

This fascinating Sahara civilization lasted from about -500 to 600 AD, and it was the time before the Islamic Conquest.

Professor Mattingly explained that 'the new evidence suggests that the early medieval expansion of trade and settlement built on earlier initiatives, in which the Garamantes had played a significant role.'

Today we know much more about the mysterious Garamantes, a long-forgotten Saharan people who made the desert region flourish, built impressive cities, and controlled an empire of 70,000 square miles.

Their houses were not primitive nomadic camps scattered across the central Sahara but sophisticated, well-organized permanent urban settlements with villages inhabited by artisans, farmers, and merchants.

Written by – A. Sutherland - AncientPages.com Senior Staff Writer

Updated on October 7, 2022

Copyright © AncientPages.com All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or part without the express written permission of AncientPages.com

Expand for referencesReferences:

Anthony R. Birley, Septimius Severus: The African Emperor

David Mattingly (ed.). Archaeology of Fezzan. Volume 1, Synthesis. London 2003

Idjennaden Bob, The Garamantes (The Forgotten Civilisations of Africa Book 4)

More From Ancient Pages

-

Ale Conner: Unpleasant And Dangerous Profession In Medieval England

Ancient History Facts | Oct 19, 2017

Ale Conner: Unpleasant And Dangerous Profession In Medieval England

Ancient History Facts | Oct 19, 2017 -

Huldra: Seductive Female Creature Living In Forest Or Mountains In Norse Beliefs

Featured Stories | Feb 8, 2018

Huldra: Seductive Female Creature Living In Forest Or Mountains In Norse Beliefs

Featured Stories | Feb 8, 2018 -

On This Day In History: Battle Of Sinop Took Place – On Nov 30, 1853

News | Nov 29, 2016

On This Day In History: Battle Of Sinop Took Place – On Nov 30, 1853

News | Nov 29, 2016 -

Flexible Glass – Lost Ancient Roman Invention Because Glassmaker Was Beheaded By Emperor Tiberius

Ancient Technology | Jul 27, 2023

Flexible Glass – Lost Ancient Roman Invention Because Glassmaker Was Beheaded By Emperor Tiberius

Ancient Technology | Jul 27, 2023 -

7,000-Year-Old Male Skeleton In Garment Decorated With Sea Shells, Red Deer Teeth Identified In France

Archaeology | Mar 9, 2017

7,000-Year-Old Male Skeleton In Garment Decorated With Sea Shells, Red Deer Teeth Identified In France

Archaeology | Mar 9, 2017 -

Struggle To Get Mail On Time Has Lasted More Than 5,000 Years – Part 1

Featured Stories | Jul 30, 2017

Struggle To Get Mail On Time Has Lasted More Than 5,000 Years – Part 1

Featured Stories | Jul 30, 2017 -

Large Mysterious 2,000-Year-Old Structure Discovered At The Center Of A Military Training Area In Israel

Archaeology | Dec 3, 2017

Large Mysterious 2,000-Year-Old Structure Discovered At The Center Of A Military Training Area In Israel

Archaeology | Dec 3, 2017 -

Mount Ararat Was Once Located By The Sea – Study Of Palm Leaves Reveals

Archaeology | Jul 18, 2020

Mount Ararat Was Once Located By The Sea – Study Of Palm Leaves Reveals

Archaeology | Jul 18, 2020 -

Jizo – Protector Of Children, Travelers And Women In Japanese Mythology

Featured Stories | Dec 23, 2015

Jizo – Protector Of Children, Travelers And Women In Japanese Mythology

Featured Stories | Dec 23, 2015 -

Mongol Empire: Rise And Fall Of One The World’s Largest And Fearsome Empires

Featured Stories | Mar 26, 2021

Mongol Empire: Rise And Fall Of One The World’s Largest And Fearsome Empires

Featured Stories | Mar 26, 2021 -

Was Mysterious 2,000-Year-Old Miniature Clay Token Used By Pilgrims Arriving To The Temple In Jerusalem?

Artifacts | Apr 26, 2024

Was Mysterious 2,000-Year-Old Miniature Clay Token Used By Pilgrims Arriving To The Temple In Jerusalem?

Artifacts | Apr 26, 2024 -

Exceptional Collection Of Well-Preserved Stucco Masks Of The Mayan Kingdom Reveal Their Secrets

Archaeology | Dec 5, 2022

Exceptional Collection Of Well-Preserved Stucco Masks Of The Mayan Kingdom Reveal Their Secrets

Archaeology | Dec 5, 2022 -

Historical Enigma Of The Ancient Werewolf Ruler – What Powers Did He Possess?

Ancient Mysteries | Jan 9, 2025

Historical Enigma Of The Ancient Werewolf Ruler – What Powers Did He Possess?

Ancient Mysteries | Jan 9, 2025 -

Mysterious Object In Asuka – The Place Of ‘Flying Birds’

Civilizations | Aug 11, 2018

Mysterious Object In Asuka – The Place Of ‘Flying Birds’

Civilizations | Aug 11, 2018 -

Pasargadae: Capital Of Achaemenid Empire Destroyed By Alexander The Great

Civilizations | Oct 24, 2016

Pasargadae: Capital Of Achaemenid Empire Destroyed By Alexander The Great

Civilizations | Oct 24, 2016 -

Modern Humans Carrying The Neanderthal Variant Have Less Protection Against Oxidative Stress

Archaeology | Jan 6, 2022

Modern Humans Carrying The Neanderthal Variant Have Less Protection Against Oxidative Stress

Archaeology | Jan 6, 2022 -

Sacrificial Remains From The Iron Age Unearthed Near Aarhus, Denmark

Archaeology | Oct 14, 2015

Sacrificial Remains From The Iron Age Unearthed Near Aarhus, Denmark

Archaeology | Oct 14, 2015 -

Unique Discovery – 2,000-Year-Old Roman Coins Found On Gotska Sandön In Sweden

Archaeology | Apr 13, 2023

Unique Discovery – 2,000-Year-Old Roman Coins Found On Gotska Sandön In Sweden

Archaeology | Apr 13, 2023 -

![Horses in the Eurasian steppes: Already 5000 years ago, they served pastoralists as a source of milk and a means of… [more] © A. Senokosov](https://www.ancientpages.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/pastoraliststeppe15-307x150.jpg) Milk Enabled Massive Steppe Migration – A New Study

Archaeology | Sep 24, 2021

Milk Enabled Massive Steppe Migration – A New Study

Archaeology | Sep 24, 2021 -

Ancient Egyptian Men Used Eye Makeup For Many Reasons

Ancient History Facts | May 9, 2016

Ancient Egyptian Men Used Eye Makeup For Many Reasons

Ancient History Facts | May 9, 2016