Surprising Evolution Discovery – Extinct Subterranean Human Species With Tiny Brains Used Fire

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - An archaeologist says he has made an astonishing discovery and can offer evidence extinct human species used fire for both light and cooking meat, despite having a much smaller brain than ours. If he is correct in his assumptions, then the archeological findings open a new surprising chapter in the history of human evolution.

The Homo naledi, a prehistoric human species that lived in underground caves in South Africa between 230,000 to 330,00 years ago. The tiny beings were about 144 centimeters tall on average and weighed around 40 kilograms. It's possible they co-existed with Homo sapiens around 300,000 years ago in Africa. The Homo naledi had a brain that was around a third of the size of a human brain.

Lee Rogers Berger holds a replica of the skull of "NEO" a new skeleton fossil findings of the Homo Naledi Hominin species. Credit: Lee Berger

The archaeological discovery discussed by South African paleoanthropologist and National Geographic explorer Lee Berger remains controversial and debated at this point. The study has not been published or peer-reviewed yet.

"We have massive evidence. It's everywhere," said Berger, who reported the findings in a press release and a Carnegie Science lecture at the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial Library in Washington last week.

"Huge lumps of charcoal, thousands of burned bones, giant hearths, and baked clay" were discovered.

"We are fairly confident to formulate the hypothesis that this small-brained hominid, Homo naledi, that existed at the same time we believe Homo sapiens were sharing parts of Africa, was using fire for a variety of purposes," he said during the lecture.

As reported by Science in Focus, "the remains of Homo naledi was first discovered in 2013 by Berger and his team hundreds of metres into a claustrophobically tight network of passages known as the Rising Star Cave system near Johannesburg, South Africa.

Subsequent excavations have since unearthed fossils from more than a dozen individuals – both male and female, juvenile and adult – as well as evidence of ritualistic burial practices in which the remains of certain individuals appear to have been washed and deliberately placed in position.

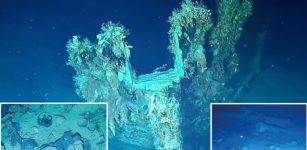

Then, earlier this year, after entering the caves himself for the first time, Berger says he noticed evidence of soot on the surfaces of the walls.

“As I looked up and stared at the roof, I began to realise that the roof was not a pure calcium carbonate. The roof above my head was greyed above fresh flowstone. There were blackened areas across the wall. There were soot particles across the whole of the surface. The entire roof of the chamber where we have spent the last seven years working is burnt and blackened,” he said.

At the same time, expedition co-director Dr. Keneiloe Molopyane, uncovered the remains of a small hearth containing burnt antelope bones flanked by the remains of a much larger hearth in a nearby cave.

Further investigation of the system then uncovered several other caves and passages with chunks of burnt wood and charred animal bones.

“Fire is not hard to find. It’s everywhere within this system,” said Berger. “Everywhere there’s a complex juncture, they built fire. Every adjacent cave system to the chambers where we believe they were disposing of the dead, they built fires and cooked animals. And in the chamber where we believe they were disposing of the dead, they built fire but didn’t cook animals. That’s extraordinary.”

The new, intriguing findings on the primitive species with a chimpanzee-like skull may fundamentally alter how we think about complex behaviors.

"We have massive evidence. It's everywhere," Berger said in an interview with New Scientist, following the lecture.

"Huge lumps of charcoal, thousands of burned bones, giant hearths and baked clay."

A hearth possibly made by Homo naledi. Credit: Lee Berger

The claims of controlled fire use have been met with skepticism from Berger's colleagues. When Homo sapiens started ti use fire to cook and provide light has long been one of the most contested questions in paleoanthropology.

Studies must first date both the evidence of fire and the bones to prove they come from the same time period, Tim D. White, director of the Human Evolution Research Center at the University of California at Berkeley, told The Washington Post in an interview.

See also: More Archaeology News

"There's a long history of claims about the use of fire in South African caves," White said.

"Any claim about the presence of controlled fire is going to be received rather skeptically if it comes via press release as opposed to data."

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer