Viking Age Shields From The Gokstad Ship Burial – Re-Examined

Conny Waters - AncientPages.com - The Gokstad ship was accidentally discovered by two curious young boys who began to dig into the mound to see if they could find anything interesting. What they found caused a sensation in Norway. Onboard the ship was a dead man. He was fully dressed and surrounded by ancient artifacts, such as a bronze kettle, runic inscriptions, a gameboard, and a sleigh.

Scientists have also recovered 64 Viking Age round shields from the Gokstad ship burial, and these ancient weapons have shaped our understanding of the past.

A reconstructive drawing of the Gokstad long ship from Nicolaysen’s 1882 publication. Drawing by Harry Schøyen. Credit: Arms & Armour (2023).

Rolf Fabricius Warming from the Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies at Stockholm University in Sweden and founding director of the Society for Combat Archaeology has spent years attempting to solve the puzzle of how Vikings and their ancestors in the Iron Age made their shields.

In a new study published in the journal Arms & Armour, Warming challenges previous interpretations of ceremonial shields found in the Gokstad 78-foot-long longship burial mound.

The identity of the Gokstad Viking Chief remains a mystery. Credit: Adobe Stock - Studio Kwadrat

Despite their significance, the shield material has never been published in full nor been subjected to any substantial examination since their discovery in 1880. The current understanding of the shields is thus highly limited. Warming notes that "despite their fragmented state, these artefacts significantly contribute to a more nuanced understanding of shield constructions of the Viking Age, especially when coupled with other well-preserved archaeological shield finds."

"For scholars interested in the Viking Age warfare, the archaeological material holds special significance, being arguably one of the main sources of data for shield technologies of this period. The remains of the reportedly 64 black and yellow painted shields uncovered at Gokstad are amongst the most well-preserved shields of the Viking Age and simply unparalleled in quantity in terms of a synchronous find from a single archaeological context.

As such, these artefacts have significantly contributed to our understanding of the construction of Viking Age round shields. It is no exaggeration to say that the finds have almost single-handedly shaped our understanding of Viking Age round shields as a consequence of their degree of preservation as well as the early excavation and publication by Norwegian archaeologist Nicolay Nicolaysen in the late 19th century," Warming writes in his study.

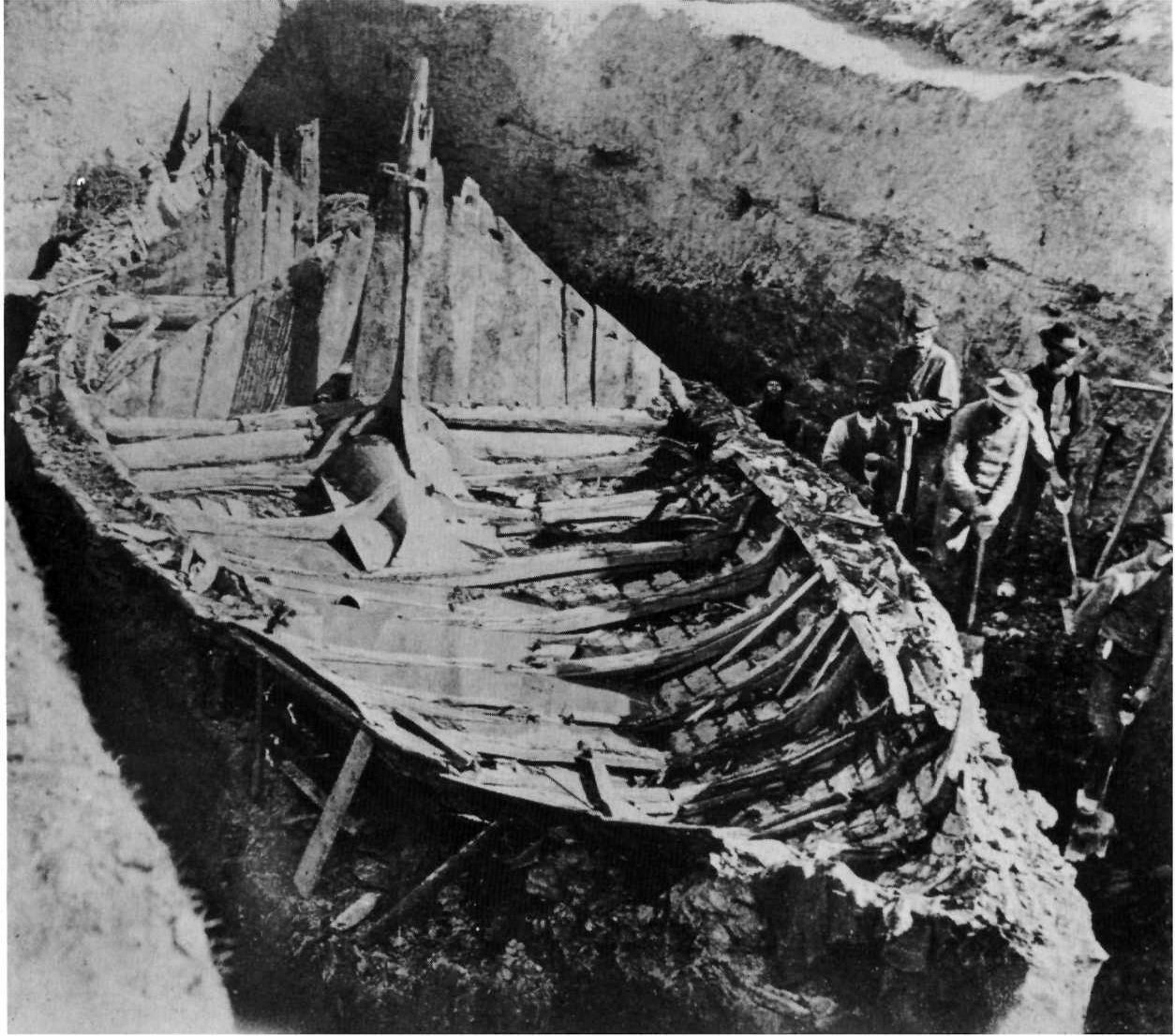

The Gokstad Viking ship in 1880 when it was discovered. Credit: Public Domain

During the excavation of the Gokstad ship, scientists found an unspecified number of shield fragments. Based on their placement, Norwegian archaeologist Nicolay Nicolaysen in 1882 suggested that "32 shields had originally hung outside on each side of the vessel between the foremost oar-port up to a little abaft the furthest sternward." The shields overlapped so that the rim of each shield touched the boss of the next. They were painted either in yellow or black and positioned in alternating colors, giving the rows of shields an appearance of yellow and black half-moons.

Each shield was circular in shape and measured 94 cm in diameter. Few studies have been conducted on these shield remains since Nicolaysen’s publication in 1882.

The surviving shield material from the Gokstad ship burial is currently kept in the collection of the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo.

Were The Viking Shields Used For Combat Or Ceremony?

Warming examined the 64-round shields that were considered constructed for a burial rite ceremony. To determine whether the Gokstad fragments represent practical or ceremonial shields, he had to study the material and craftmanship in general.

An important question in this respect is whether the shields were reinforced with skin product. The presence of animal skins on shields would indicate functional constructions for use in combat. Warming also explains that the parchment could have been painted, which might explain why pigments were not detected on the board fragments, as a thin organic covering might not have survived.

It is possible the shields were "constructed for the purpose of being used in combat. On the other hand, it is equally important to note that any potential repairs could also have been undertaken in the original construction process and that some faulty material may have been permissible if the shields were mostly for visual display."

Warming points out more studies must be carried out to determine whether the shields were used for warfare or ceremonial purposes, or both. "Given the strong association with the ship, it would also be pertinent to re-examine shield material from other ship burials for similar indications.

"To better understand the shield assemblage, it will be important to examine the cultural biographies of the objects. For now, it is sufficient to say that the heterogenous nature of the shield assemblage needs to be addressed and can either be interpreted as a consequence of their use in life or the funerary rite.

In examining the wooden shield fragments from the Gokstad ship burial, this study highlights the need for a more nuanced interpretation of these artefacts and serves as useful reminder of the complexity of Viking Age shield technologies.

Most significantly, the investigation shows that the shield material reflects a high degree of uniformity but also important differences beyond the use of pigments, including constructional features that strongly suggest a functional use of the shields, although certain features can potentially be ascribed to shields of a ceremonial nature.

This assessment forms a cogent argument for discarding past interpretations of these shields as being merely ceremonial as well as the overarching dichotomous discussion of whether all the 64 shields are necessarily either for ceremony or combat.

Shield ‘reconstruction’ cobbled together in the late 19th - early 20th century. The shield is reinforced with modern steel frames but comprised of original boards. The central board is seemingly equipped with a roughly heart-shaped centre hole. Photo: © Museum of Cultural History, University of Oslo, Norway. Rotated 90 degrees clockwise by the author.

It is assumedly partly because of the underappreciation of the complexity of the shields and the underlying assumption of homogeneity that many constructional details have been overlooked since Nicolaysen’s excavation in 1880. Although only a brief and preliminary investigation, the present study has thus brought forth a number of significant considerations and points of departure for future studies. The Gokstad shield material has yet to be published in full and much of the material should be subjected to re-examination, where careful attention is paid to the craftsmanship, the thin patches of organic material on some of the boards and details that can connect the various fragments, although the reassembly of a complete shield is unlikely.

With a much richer body of literature available on round shields today than at the time of their excavation, it will also be important to compare the constructional details of the Gokstad shields to other archaeological finds and the Germanic flat round shield tradition in general.

When carefully examined, the wooden fragments can continue to animate our understanding of the construction and roles of shield technologies of the Viking Age as well as funeral rites in general. The devil is in the detail and the pagan ship burial at Gokstad has fortunately left us many to examine," Warming concludes in this study.

The study was published in the journal Arms & Armour

Written by Conny Waters - AncientPages.com Staff Writer