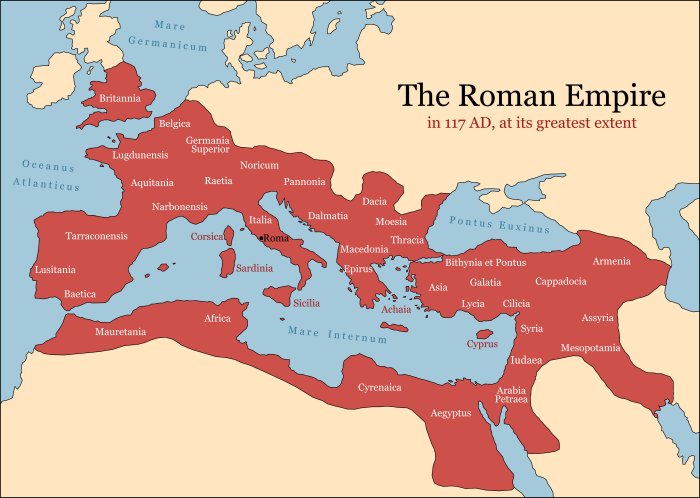

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - Ruled by many Emperors, the mighty and vast Roman Empire covered territories that included Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia. Established in 27 B.C. following the demise of the Roman Republic, the first Roman Emperor, August, opened a new and everlasting chapter in the history of Rome and everyone who came in contact with the Roman Empire.

Throughout the thousand-year reign of the Roman Empire, people crossed borders and moved to new places, but where did these individuals come from? A new DNA study of genetic material from ancient skeletons offers a detailed picture of travel and migration patterns during the Empire's height.

Credit: Adobe Stock - Peter Hermes Furian

An international team of scientists led by Stanford medicine researchers analyzed the DNA of thousands of ancient humans, including 204 who had not been previously sequenced.

What Can Ancient DNA Reveal About Roman Era Mibility?

The results of the study published 'in eLife reveal at least 8% of the studied individuals 'did not originally come from the area of Europe, Africa, or Asia in which they were buried.

"Until now, we had to rely on the historical and archaeological record to try to piece together how the population was interacting and changing during this time," said Jonathan Pritchard, Ph.D., a professor of genetics and biology and one of the paper's senior authors. "Now, we can add new details from a genetic perspective."

In a previous study, Pritchard used ancient DNA to study the genetic diversity of people in and around Rome during a 12,000-year swath of history spanning the Stone Age to medieval times.

Researchers discovered ancient people were mobile and not reluctant to move further away from their point of origin. Around 783 B.C. Rome rapidly grew more diverse, especially during its official founding.

The science team was interested in exploring how much of that diversity was unique to Rome, the capital of the empire, and how diverse more remote areas might have been. To gain a more comprehensive overview of the situation, they narrowed the window of time from the conclusion of the Iron Age 3,000 years ago to today—but looked at a geographic area covering the entire Roman Empire.

The new study relied on existing DNA from thousands of ancient skeletons unearthed in Central Europe, Eastern Europe and Central Asia, Britain and Northern Europe, and North Africa. The research team additionally sequenced 204 new genomes from 53 archaeological sites in 18 countries. Most were from individuals who died during the periods known as imperial Rome and late antiquity, from the first to seventh centuries B.C.

One of the first things the researchers observed was that during this period, there was less diversity in areas surrounded by mountains, such as the Armenian highlands, where few people could be linked to the Roman Empire. Overall, however, most areas of the Roman Empire had skeletons from a variety of genetic origins. Particularly diverse areas included Sardinia, the Balkans, and parts of central and western Europe.

"In contrast to the homogeneity of the Armenian population, most of the regions, including Italy, Southeastern Europe, and Western Europe, had strikingly heterogeneous populations. Newly collected samples reinforce previous findings of high heterogeneity in Rome, including a large portion of the population having affinities for present-day Near Eastern populations. Interestingly, Southeastern European and Western European individuals during the Imperial Roman & Late Antiquity period also exhibit high heterogeneity, on par with that of contemporaneous Italy," the scientists write in their study.

"For the most part, the observations complement what historians and archaeologists hypothesized," said Margaret Antonio, a graduate student in the Pritchard lab and co-first author of the paper. "For example, North African pottery was found throughout the Roman Empire. Now, we also find genetic evidence of people from North Africa residing in present-day Italy and Austria."

The next step was to understand which areas were connected. This was accomplished by a large genetic analysis of the people unearthed at every location whose genetic ancestry didn't match where they were found, suggesting that they or their recent ancestors had traveled or migrated.

The research team discovered that there were common patterns of ancestry among people not local to where they were found. People found in Britain and Ireland were most likely to be from northern or central Europe, for instance, and far less likely to come from southwestern Europe or North Africa. The study helped scientists to explain how trade routes and military movements could have fueled the diversity during the Roman Era.

"The expansion of the empire was a huge undertaking requiring thousands of troops with trade, labor, slavery, and forced displacement," Clemens Weiss, Ph.D., a former postdoctoral fellow in the Pritchard lab who co-led the work, said. "As the empire expanded, it pulled in more and more people and increased mobility across entire continents."

According to researchers, the increase in mobility can be understood as a sign people were traveling across a continent for the first time in their lives.

A Puzzling Roman Conundrum

The genetic data confronted scientists with intriguing questions and observations. If people had continued to move around at the rate seen during the studied period, the regional differences would have gradually begun to disappear. The genomes of people in Eastern Europe, for instance, would have become indistinguishable from those in Western Europe and North Africa and vice versa. However, most of these populations have remained genetically distinct until this day.

Timeline of new and published genomes. (A) 204 newly reported genomes (black circles) are shown alongside published genomes (gray circles), ordered by time and region (colored the same way as in B). (B) Sampling locations of newly reported (black) and published (gray) genomes are indicated by diamonds, sized according to the number of genomes at each location. Credit: eLife (2024). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.79714

"We observed largely stable spatial population structure across western Eurasia and high mobility of people evidenced by local genetic heterogeneity and cross-regional connections. These two observations are seemingly incompatible with each other under standard population genetics assumptions," the research team wrote in their study.

Could the reason be people were not always reproducing in the locations where they died, and some may have traveled during their lifetimes but returned home before having children?

"A possible explanation for this apparent paradox is that our simulations did not capture some key features of human behavior and population dynamics. In the simulated populations, migration implies both movement and reproduction with local random mate choice. However, in real human populations migration can be more complex: people do not necessarily reproduce where they migrate, and reproduction is not necessarily random. We hypothesize that in the historical period there was an increasing decoupling of movement and reproduction, compared to prehistoric times," the science paper informs.

"All we can say for sure is where these people died," Weiss said. "If someone died during a military deployment, it doesn't mean they had resettled permanently to the area where their body was found."

Another hypothesis researchers considered is that the mobility of people drastically declined when the Roman Empire collapsed. Unfortunately, the lack of data from this time frame prevents scientists from pursuing this line of thought.

The study's results are nevertheless intriguing as they give us a glimpse into just how mobile people were during the Roman Empire.

See also: More Archaeology News

"It shows that movement isn't new; people in the Roman Empire were really traveling in much the same way we do now," Antonio said. "They moved for trade and for work. Some people settled where they moved, and others did not."

"This work highlights the utility of ancient DNA in revealing complex population dynamics through direct genetic observations through time and the importance of integrating historical contexts to understand these complexities," the scientists concluded.

The study was published in the journal eLife

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer