Fire-Burning Event At The Maya Kingdom Of K’anwitznal Was A Reaction To Regime Change

Conny Waters - AncientPages.com - Throughout history, it is inevitable that all leaders will eventually succeed. However, ancient civilizations' responses to these transitions of power varied greatly.

Recent archaeological research in Guatemala has provided new insights into the political durability of the ancient Maya civilization. This research challenges earlier assumptions that the ancient Maya were simply passive observers of their dynastic systems' decline during the end of the Classic period. Instead, it reveals that they actively reshaped their political structures, laying a foundation for innovative governance models.

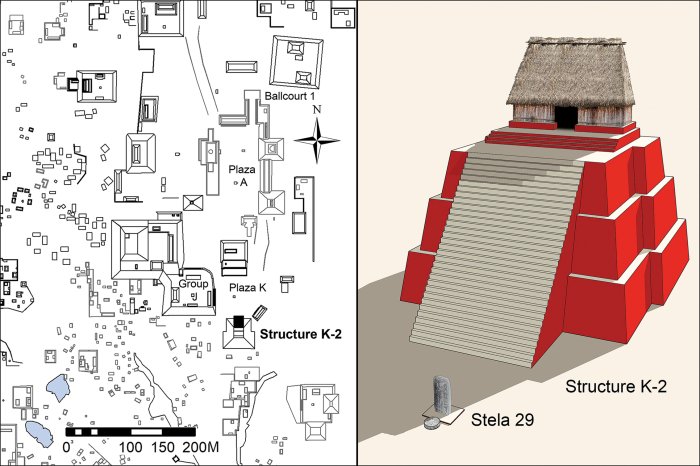

Left - plan of part of the Ucanal site core showing the location of Structure K-2; Right - illustrated reconstruction of Structure K-2 in its final phase (reconstruction by L.F. Luin) . Credit: Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.38

Recent archaeological findings have shed light on the practices of the early ninth-century AD Maya civilization. At a pyramid in Ucanal, Guatemala, evidence of ritualistic burning of royal human remains has been discovered. This suggests that such events were public demonstrations associated with political regime changes.

Historical texts point towards a period of significant political turbulence in the Maya Lowlands at the start of the ninth century AD. However, it also marks a time when the Maya kingdom of K'anwitznal began to rise in political prominence. This ascent coincided with the reign of a potentially foreign leader named Papmalil, indicating his possible role in this power shift.

Much epigraphic and archaeological research in the Maya area has focused on the collapse of Classic Maya polities at the end of the eighth and the beginning of the ninth century A.D.

However, key tipping points in history are rarely found directly in the archaeological record," states the lead author of the research, Dr. Christina T. Halperin, from the University of Montreal.

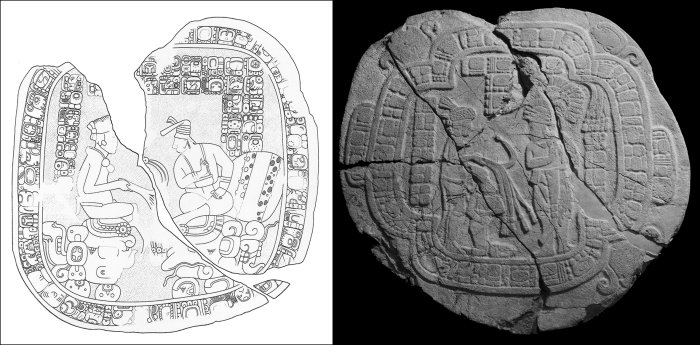

Left - illustration of Caracol Altar 12 showing Papmalil of K'anwitznal seated across and left from Caracol ruler, K'inich Toobil Yopaat, AD 820 (drawing by N. Grube, used with permission); right - Caracol Altar 13 showing Papmalil standing left of Caracol ruler, K'inich Toobil Yopaat, AD 820.

Credit: Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.38

Dr. Halperin, along with a group of researchers, conducted an excavation at a temple pyramid located in the K'anwitznal capital of Ucanal. They unearthed a deposit that held burnt human remains and various ornaments. Among these objects were numerous personal adornments crafted from precious materials. Notably, a greenstone mask typically found in royal tombs alongside the deceased ruler was found. This evidence leads to the inference that the burial site likely belonged to Maya royalty.

Radiocarbon dating provides evidence that a significant burning event likely occurred between AD 773 and 881 after the death of the royal individuals. This suggests that there was a deliberate re-entry into the tomb to burn these royal remains. The ashes were then used to build a new temple pyramid phase.

This act of burning is believed to be politically motivated, symbolizing the rejection of an existing Late Classic (ca. 600–810 CE) Maya dynasty and the ushering in of a new political era on the brink of the Terminal Classic period. This public spectacle coincided with Papmalil's ascension to power over the kingdom.

The practice of re-entering tombs and incinerating royal remains is documented in Mayan hieroglyphic texts. Historically, this act has been perceived as a form of desecration. Moreover, the timing of these ritualistic fire-burning events aligns with the large-scale deconstruction and repurposing of elite structures at Ucanal.

Carved pendant plaque of a human head from the burial. Credit: C. Halperin

"The fire-burning event of the burial deposit was likely a dramatic public affair. Because the fire-burning event itself had the potential to be highly ceremonial, public and charged with emotion, it could dramatically mark the dismantling of an ancient regime.

The fire-burning event itself and the reign of Papmalil helped usher in new forms of monumental imagery that emphasized horizontal political ties and fundamental changes in the social structure of society," states Dr. Halperin.

See also: More Archaeology News

In this sense, it was not just an end of an era, but a pivot point around which the K'anwitznal polity, and the Maya of the southern Lowlands in general, transformed themselves anew," says Dr. Halperin.

The study was published in the journal Antiquity

Written by Conny Waters - AncientPages.com Staff Writer