Ice Age Mystery – Unexplained Disappearance Of North America’s Large Mammals – New Clues

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - North America was once a realm dominated by megafauna, colossal creatures that roamed the land during the last ice age, approximately 50,000 years ago. The tundra was traversed by lumbering mammoths, while towering mastodons, fierce saber-toothed tigers, and enormous wolves inhabited the forests.

Vast herds of bison and extraordinarily tall camels migrated across the continent, and giant beavers thrived in its lakes and ponds. Immense ground sloths, weighing over 1,000 kg, were found across many regions east of the Rocky Mountains.

USNM 23792, Mammuthus primigenius, or Wooly Mammoth (composite), Department of Paleobiology, Smithsonian Institution. Credit: Gary Mulcahey.

However, most of North America's megafauna mysteriously disappeared towards the end of the Last Ice Age. The precise causes and mechanisms behind this extinction event remain a subject of intense debate among researchers. One theory suggests that the arrival of humans played a pivotal role, either through hunting and consumption of these animals or by altering their habitats and competing for vital food sources.

Other researchers contend that climate change was the culprit behind the extinction of megafauna. They argue that as the Earth thawed after several thousand years of glacial temperatures, the rapid environmental changes outpaced the ability of these large animals to adapt. This contrasting viewpoint has led to intense disagreements and heated debates between the two schools of thought.

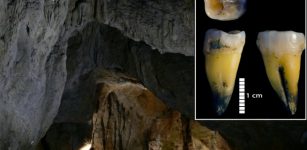

Despite decades of research, the mystery surrounding the megafaunal extinction during the Ice Age remains unresolved. Currently, researchers lack sufficient evidence to conclusively rule out one scenario or the other, or even other proposed explanations, such as disease, a comet impact event, or a combination of factors. One of the challenges lies in the fragmented and deteriorated state of many megafaunal bones used to track their presence.

While some sites have preserved megafaunal remains remarkably well, others have subjected the animal bones to harsh conditions, causing them to break down into smaller fragments that are too altered for identification. These decay processes include exposure to the elements, abrasion, breakage, and biomolecular degradation.

Such problems lack critical information about where particular megafaunal species were distributed, when they precisely disappeared, and how they responded to humans' arrival or the climatic alteration of environments in the Late Pleistocene.

A new study published in Frontiers in Mammal Science may shed new light on this Ice Age mystery.

Scientists have focused on the exceptional Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collections in Washington, DC. This museum houses the findings from numerous archaeological excavations conducted over the past century, making it an extraordinary repository of animal bones that are deeply relevant to understanding the extinction of North America's megafauna.

However, many of these remains are heavily fragmented and unidentifiable, which has limited their ability to shed light on this question until now. Fortunately, recent years have witnessed the development of new biomolecular methods of archaeological exploration. Instead of embarking on new excavations, archaeologists increasingly turn to scientific laboratories, utilizing new techniques to probe existing material.

Credit: Adobe Stock - Ellionn

One such novel technique is ZooMS—short for Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry. The method relies on the fact that while most of its proteins degrade quickly after an animal dies, some, like bone collagen, can be preserved over long time periods.

Since collagen proteins frequently differ in small, subtle ways between different taxonomic groups of animals and even individual species, collagen sequences can provide a kind of molecular barcode to help identify bone fragments that are otherwise unidentifiable.

So, collagen protein segments extracted from minute quantities of bone can be separated and analyzed on a mass spectrometer to identify remnant bones that traditional zooarchaeologists cannot.

Using an innovative method, researchers embarked on a pioneering study to explore the Smithsonian Museum's archived bone material. This pilot study addressed a crucial question: would the bones housed in the museum's collection preserve sufficient collagen to enable further insights into the fragmented bone material stored in its storerooms?

The answer was not immediately apparent, as many excavations occurred decades ago. Although the material had been stored in a state-of-the-art, climate-controlled facility for the past decade, the early dates of the excavations raised concerns about whether modern standards were consistently applied during handling, processing, and storage at all stages.

The research team meticulously examined bone material from five archaeological sites, all dating back to the Late Pleistocene/earliest Holocene period (approximately 13,000 to 10,000 calendar years before present) or earlier. These sites were located in Colorado, in the western United States, with the earliest excavation occurring in 1934 and the latest in 1981.

The material from the sites was often fragmented, lacking features that could enable zooarchaeological identification. Some bone fragments were bleached, weathered, or edge-rounded, suggesting transport by water or sediment before burial at the site.

The recent scientific findings regarding analyzing ancient bone collections have provided valuable insights. Despite the challenges posed by the materials' age, appearance, and origins, the ZooMS (Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry) technique yielded remarkable results. Approximately 80% of the sampled bones contained sufficient collagen for identification, with 73% being identified at the genus level.

The taxa identified through ZooMS included Bison, Mammuthus (the genus of mammoths), Camelidae (the camel family), and possibly Mammut (the genus of mastodons). In some cases, the specimens could only be assigned to broader taxonomic groups due to the lack of comprehensive ZooMS reference libraries for North American animals. These databases, which are relatively well-developed for Eurasia but not for other regions, are essential for accurately identifying the spectra produced by mass spectrometry analysis.

The findings have significant implications for museum collections. The materials studied by the researchers are often overlooked in favor of more visually appealing specimens typically displayed in natural history museums. However, this study demonstrates the valuable information that can be gleaned from these seemingly unimpressive collections through advanced analytical techniques like ZooMS.

1961 excavation at Lamb Spring, showing Ed Lewis (standing on left) and Waldo Wedel, along with two fieldmen. Glenn Scott can be seen in the excavation pit alongside some mammoth bones wrapped in plaster jackets for preservation. Credit: USGS public domain image.

ZooMS, or Zooarchaeology by Mass Spectrometry, is a groundbreaking technique that has the potential to provide invaluable research data to address long-standing questions surrounding the extinction of megafauna. This research highlights the importance of preserving archaeological collections, as even seemingly insignificant artifacts or bones can prove invaluable information sources in the future. When faced with limited funding, institutions may neglect or discard materials that do not appear immediately beneficial, which is a critical issue. Museums and research facilities must be adequately funded to ensure the proper care and long-term preservation of archaeological remains.

This analysis demonstrates that old materials can find new life unexpectedly, allowing researchers to utilize tiny bone fragments to unravel mysteries, such as the disappearance of some of the largest animals that once roamed ancient North America.

The study was published in Frontiers in Mammal Science

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer