Scientists Suggest Neanderthals And Modern Humans Should Be Classified As Separate Species

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - A recent study by researchers from London's Natural History Museum and the Institute of Philosophy at KU Leuven has strengthened the argument that Neanderthals and modern humans (Homo sapiens) should be classified as separate species to more accurately trace our evolutionary history.

While definitions of what constitutes a species vary among researchers, it is widely accepted that both H. sapiens and Neanderthals share a common ancestral species. However, ongoing research into Neanderthal genetics and evolution has rekindled discussions about whether they should be considered distinct from H. sapiens or categorized as a subspecies (H. sapiens neanderthalensis).

Chris Stringer from the Natural History Museum in London and Andra Meneganzin from KU Leuven's Institute of Philosophy advocate for classifying them as separate species. They argue that despite the limitations inherent in fossil records, there is sufficient morphological, ecological, genetic, and temporal evidence to support this classification. This evidence highlights the complexity of speciation processes, where populations diverge over time to become distinct descendant species.

The researchers suggest that taxonomic disagreements are better understood through how speciation processes are represented in records rather than through conflicts between different types of evidence.

In the science of human origins, implicit and unrealistic theoretical assumptions can be just as limiting as the scarcity of data. Taxonomic disagreement over the classification of our species and Neanderthals offer a prime example of oversimplified expectations regarding the nature of speciation. Both in present and past taxa, speciation unfolds across space and time, through multiple stages involving the incremental acquisition of distinct characters.

"By reading the fossil records through the temporal and geographic dimensions that shaped past human diversity, available data can become increasingly informative rather than more limiting, and help move debates beyond unproductive deadlock," Dr. Meneganzin, Post-doctoral Fellow at the KU Leuven Institute of Philosophy and lead author of the study, says.

"In the context of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens, we need to regard speciation as a gradual process that occurred over more than 400,000 years. It is correct that the two interbred where they were not geographically separate, but over time differentiation continued to a point where the two were distinctly different species.

"When the Neanderthals died out around 40,000 years ago, the two species were in the final stage of the speciation process and were developing reproductive isolation from each other," Professor Stringer, Research Leader at the Natural History Museum and joint author of the paper, says.

Mapping speciation over a 400,000-year span using paleontological and archaeological evidence presents notable challenges for scientists. This complexity stems from the fact that during the later stages of speciation, Homo sapiens and Neanderthals continued to interbreed, sharing genes and behaviors. To accurately trace modern human evolution, it is crucial to categorize anatomical and geographical developments.

The study highlights that if interbreeding were the sole criterion for determining species status, many distinct species of mammals and birds today would lose their separate classifications. Recognizing evolutionary patterns through categorization is essential; otherwise, pinpointing when a species first emerged becomes increasingly difficult.

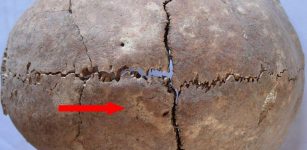

A replica of an approximately 50,000-year-old Neanderthal cranium from La Ferrassie, France, compared to a recent Homo Sapiens cranium. Credit: Trustees of the Natural History Museum

Fossil records indicate that Homo sapiens originated in Africa while Neanderthals evolved in Eurasia over at least 400,000 years. Interbreeding occurred as Homo sapiens expanded from Africa. However, the study argues that by this time of expansion and subsequent interbreeding, sufficient differentiation had occurred between the two groups to classify them as distinct species. Notably, their ecological profiles differed enough to associate them with "minimally different" habitats.

Neanderthals were particularly adapted to colder climates—an adaptation not yet fully achieved by humans without technological aid today. They required higher physical activity levels for extended periods to gather necessary resources for survival. This need explains various morphological differences such as ribcage and pelvis shapes which suggest larger internal organs like lungs, heart, and liver among other anatomical distinctions.

See also: More Archaeology News

The more gracile skeleton of Homo sapiens may have contributed to their survival, as it indicates a more economical physiology that required fewer energy and resources. This advantage, combined with the use of complex technology, could have been crucial during periods of rapid climate change or intense competition for resources when they coexisted with other species.

This area of research continues to evolve, and a recent paper aims to establish a clear theoretical framework for future studies. It emphasizes the need for a detailed chronological and evolutionary analysis of the existing fossil record to enhance our understanding.

The study was published in Evolutionary Journal of the Linnean Society

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer