Conny Waters - Ancient Pages.com - Around 700 B.C., the Neo-Assyrian emperor Sargon II embarked on an ambitious project to build a new capital city in the desert of what is now Iraq. This city, named after himself, was thought to have been abandoned shortly after construction began, leaving behind only ruins.

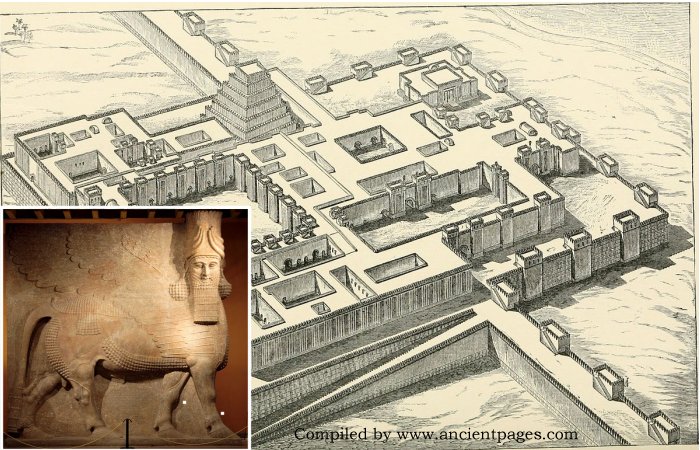

Reconstructed Model of Palace of Sargon at Khosrabad 1905. Credit: Internet Archive Book Images - Public Domain. Bottom left: A human-headed winged bull known as a lamassu from Dur-Sharrukin. Neo-Assyrian Period, ca. 721–705 B.C. Credit: Trjames - CC BY-SA 3.0 Image compilation - AncientPages.com

However, recent findings challenge this long-held belief. A newly published survey using precision magnetometer data has revealed previously unknown buildings and infrastructure within the city walls. This compelling evidence suggests that Dur-Sharrukin (“Fortress of Sargon”), now known as Khorsabad, flourished beyond just its palace.

Sargon II passed away a few years into the construction of Dur-Sharrukin. His son then established his own capital in Nineveh, causing Sargon's project to fade from memory for over two millennia. In the 1800s, French archaeologists rediscovered Khorsabad and unearthed treasures from Sargon's palace that showcased Neo-Assyrian art and culture.

Yet excavations elsewhere yielded no significant finds, leading experts to conclude that only the palace had been constructed within Khorsabad's expansive walls.

Now is the time to reconsider this narrative with fresh eyes and embrace these groundbreaking discoveries that reveal a once-thriving metropolis hidden beneath centuries of history.

When the two-year occupation of Khorasbad by the Islamic State concluded in 2017, a remarkable opportunity arose for the French Archaeological Mission at Khorsabad to embark on an ambitious project. Their goal was not only to assess visible damage but also to conduct the first-ever geophysical survey of buried remains at this historic site. This initiative promised to uncover crucial aspects of the city's water infrastructure, provide new insights into its fortifications, and potentially reveal traces of settlements beyond the palace grounds.

In 2022, Jörg Fassbinder from Ludwig-Maximilians-University joined forces with experts from Near Eastern Archaeology, Panthéon Sorbonne University, and the University of Strasbourg. Together, they mapped approximately 7% of Khorasbad using a high-resolution magnetometer—an instrument that acts like an X-ray for underground features. By detecting distinct magnetic properties in different materials such as limestone pavements and ancient baked bricks, they gained unprecedented insights into what lies beneath.

To ensure their work remained discreet amid regional instability, Fassbinder's team opted for a low-profile approach. Rather than using drones or vehicles that might draw unwanted attention, they carried their 33-pound (15-kilogram) instruments by hand across vast stretches of land—covering an impressive area of 2.79 million square feet in long straight lines over seven days. Each day involved walking more than 13 miles (20 kilometers), demonstrating their unwavering dedication.

Credit: NS14A-03 Blue prints of the Assyrian Empire: Magnetic traces of Khorsabad, capital of Sargon II

The results were undeniably worth every step taken during this exhaustive survey effort. This groundbreaking research not only enriches our understanding but also underscores why supporting such initiatives is vital for preserving our shared heritage and unlocking history's hidden secrets.

"Every day we discovered something new," Fassbinder said in a press release. When the data were visualized as grayscale images, ghostly outlines emerged of structures as deep as six to ten feet (two to three meters) below ground. The data revealed the location of the city's water gate, possible palace gardens, and five enormous buildings, including a 127-room villa twice the size of the U.S. White House. These and other discoveries are evidence that, at least for some time, Khorsabad was a living city.

See also: More Archaeology News

"All of this was found with no excavation," Fassbinder pointed out. "Excavation is very expensive, so the archaeologists wanted to know in detail what they could expect to achieve by digging. The survey saved time and money. It's a necessary tool before starting any excavation."

Written by Conny Waters - AncientPages.com Staff Writer