12,000-Year-Old Archaeological Evidence Of Human-Dog Friendship In Alaska

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - The phrase "Dog is man's best friend" might be an old cliché, but when that friendship began is a longstanding question among scientists.

Recent research led by a University of Arizona scholar offers new insights into how Indigenous peoples in the Americas engaged with early dogs and wolves.

Credit: Pixabay - giselastillhard - Public Domain

Published in the journal Science Advances, this study examines archaeological remains from Alaska and reveals that humans and the ancestors of modern dogs began establishing close bonds as far back as 12,000 years ago—approximately 2,000 years earlier than previously documented in the Americas.

"We now have evidence that canids and people had close relationships earlier than we knew they did in the Americas," said lead study author François Lanoë, an assistant research professor in the U of A School of Anthropology in the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences.

"People like me who are interested in the peopling of the Americas are very interested in knowing if those first Americans came with dogs," Lanoë added. "Until you find those animals in archaeological sites, we can speculate about it, but it's hard to prove one way or another. So, this is a significant contribution."

In 2018, Lanoë and his team discovered a tibia, or lower-leg bone, of an adult canine at the Swan Point archaeological site in Alaska, located about 70 miles southeast of Fairbanks. Radiocarbon dating revealed that this canine lived approximately 12,000 years ago, towards the end of the Ice Age. Further research in June 2023 uncovered an 8,100-year-old canine jawbone at Hollembaek Hill near Delta Junction. Both findings suggest possible domestication.

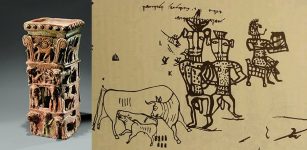

François Lanoë, an assistant research professor in the U of A School of Anthropology, after helping unearth this 8,100-year-old canine jawbone in interior Alaska in June 2023. The bone, along with a 12,000-year-old leg bone discovered at a nearby site, are some of the earliest evidence that ancient dogs and wolves formed close relationships with people in the Americas. Credit: Zach Smith

Chemical analyses indicated significant salmon protein presence in both bones, suggesting these canines regularly consumed fish—a diet uncommon for canines in that region during those times as they primarily hunted land animals. The most plausible explanation for this dietary shift is their dependence on humans for food sources.

"This is the smoking gun because they're not really going after salmon in the wild," said study co-author Ben Potter, an archaeologist with the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Researchers unearthed this 8,100-year-old canine jawbone in interior Alaska in June 2023. The bone, along with a 12,000-year-old leg bone discovered at a nearby site, are the earliest evidence that ancestors of today's dogs formed close relationships with people in the Americas. Credit: Zach Smith

The researchers are confident that the Swan Point canine helps establish the earliest known close relationships between humans and canines in the Americas. However, it's too early to determine if the discovery represents the earliest domesticated dog in the Americas.

This is why the study is valuable, Potter said, "It asks the existential question, what is a dog?" According to Lanoë, the Swan Point and Hollembaek Hill specimens may be too old to be genetically related to other known, more recent dog populations.

"Behaviorally, they seem to be like dogs, as they ate salmon provided by people," Lanoë said, "but genetically, they're not related to anything we know."

He noted that they could have been tamed wolves rather than fully domesticated dogs.

The jawbone and the leg bone, seen here in a composite scan, both showed substantial contributions from salmon proteins in lab testing, leading researchers to conclude that humans had fed the fish to the dogs. Credit: François Lanoë/University of Arizona School of Anthropology

The study is part of a long partnership with Alaska's Tanana Valley tribal communities, where archaeologists have worked since the 1930s, said co-author Josh Reuther from the University of Alaska Museum. Researchers present their plans to the Healy Lake Village Council, representing the Mendas Cha'ag people, before studies. The council approved genetic testing for new specimens. Evelynn Combs, a Healy Lake member who grew up exploring dig sites in the Tanana Valley and learning from archaeologists like Lanoë, Potter, and Reuther, is now an archaeologist at the tribe's cultural preservation office.

Researchers unearthed the jawbone at a site called Hollembaek Hill, south of Delta Junction, a region where archaeologists have long done research in partnership with local tribes. Credit: Joshua Reuther

"It is little—but it is profound—to get the proper permission and to respect those who live on that land," Combs said.

Healy Lake members, Combs said, have long considered their dogs to be mystic companions. Today, nearly every resident in her village, she said, is closely bonded to one dog. Combs spent her childhood exploring her village alongside Rosebud, a Labrador retriever mix.

See also: More Archaeology News

"I really like the idea that, in the record, however long ago, it is a repeatable cultural experience that I have this relationship and this level of love with my dog," she said.

"I know that throughout history, these relationships have always been present. I really love that we can look at the record and see that, thousands of years ago, we still had our companions."

The study was published in the journal Science Advances

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer