Remarkable Skill Of Ancient Peru’s Cranial Surgeons

AncientPages.com - Thousands of years, trepanation—the act of scraping, cutting, or drilling an opening into the cranium—was practiced around the world, primarily to treat head trauma, but possibly to quell headaches, seizures and mental illnesses, or even to expel perceived demons.

A new study shows that trepanation practiced in ancient Peru with the survival rate for the procedure during the Incan Empire was about twice that of the American Civil War—when, more three centuries later, soldiers were trepanned presumably by better trained, educated and equipped surgeons.

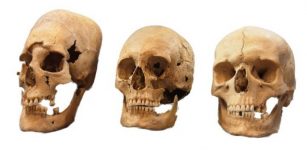

Trepanned skull from ancient Peru. The operation has been performed by means of a series of incisions placed at right angles to each other. Credits: cambridge.org

“There are still many unknowns about the procedure and the individuals on whom trepanation was performed, but the outcomes during the Civil War were dismal compared to Incan times,” David Kushner from the University Of Miami Miller School Of Medicine, who led the study, said in a press release.

“In Incan times, the mortality rate was between 17 and 25 percent, and during the Civil War, it was between 46 and 56 percent. That’s a big difference. The question is how did the ancient Peruvian surgeons have outcomes that far surpassed those of surgeons during the American Civil War?”

According to the study, which relied on Verano’s extensive field research on trepanation over a nearly 2,000-year period in Peru and a review of the scientific literature about trepanation around the world, Civil War surgeons often used unsterilized medical tools and their bare fingers to probe open cranial wounds or break up blood clots.

“If there was an opening in the skull they would poke a finger into the wound and feel around, exploring for clots and bone fragments,” Kushner said, adding that nearly every Civil War soldier with a gunshot wound subsequently suffered from infection.

More ancient skulls bearing evidence of trepanation—a telltale hole surgically cut into the cranium—have been found in Peru than the combined number found in the rest of the world. Image credit: University of Miami

“We do not know how the ancient Peruvians prevented infection, but it seems that they did a good job of it. Neither do we know what they used as anesthesia, but since there were so many (cranial surgeries) they must have used something—possibly coca leaves. Maybe there was something else, maybe a fermented beverage. There are no written records, so we just don’t know.”

Whatever their methods, ancient Peruvians had plenty of practice.

More than 800 prehistoric skulls with evidence of trepanation—at least one but as many as seven telltale holes—have been found in the coastal regions and the Andean highlands of Peru, the earliest dating back to about 400 B.C.

That’s more than the combined total number of prehistoric trepanned skulls found in the rest of the world.

See also:

Prehistoric Surgery: Skull Operations Technically Superior To Our Own

The long-term survival rates from such “shallow surgeries” in Peru during those early years, from about 400 to 200 B.C., proved to be worse than those in the Civil War, when about half the patients died. But, from 1000 to 1400 A.D., survival rates improved dramatically, to as high as 91 percent in some samples, to an average of 75 to 83 percent during the Incan period, the study showed.

“Over time, from the earliest to the latest, they learned which techniques were better, and less likely to perforate the dura,” said Kushner, who has written extensively about modern-day neurosurgical outcomes.

“They seemed to understand head anatomy and purposefully avoided the areas where there would be more bleeding. They also realized that larger-sized trepanations were less likely to be as successful as smaller ones. Physical evidence definitely shows that these ancient surgeons refined the procedure over time. Their success is truly remarkable.”

The stuty also shows how ancient Peruvians significantly refined their trepanation techniques over the centuries. They learned, for example, not to perforate the protective membrane surrounding the brain—a guideline Hippocrates codified in ancient Greece at about the same time, 5th century, B.C., that trepanning is thought to have begun in ancient Peru.

AncientPages.com