Ancient Mummy Of ‘Hatason’: Woman Who Died In Egypt More Than 3,000 Years Ago – Stanford Radiologists Investigate

AncientPages.com - Thousands of years ago lived a woman in the Egyptian city of Asyut, on the west side of the Nile River Valley, 375 miles south of the Mediterranean city of Alexandria. Her true name is unknown, but today some call her Hatason.

Now, a 3,200-year-old Egyptian mummy - currently housed at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco - was transported to the Stanford University School of Medicine for a computed tomography (CT) scan.

When Hatason died, someone took the time to mummify her. Her coffin depicts a woman in everyday clothes. But did her mummified remains originally belong in that coffin? Stanford Egyptologist Anne Austin explained.

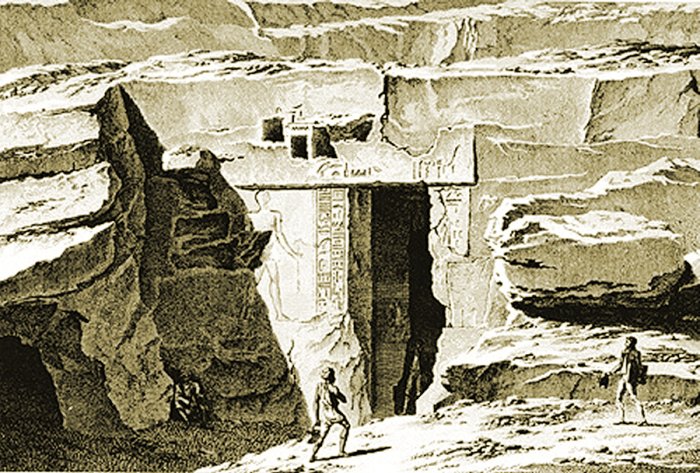

Ancient Asyut was the capital of the Thirteenth Nome of Upper Egypt (Lycopolites Nome) around 3100 BCE. It was located on the western bank of the Nile. The two most prominent gods of the Ancient Egyptian Asyut were Anubis and Wepwawet, both funerary deities. Credits: Wikipedia

“When mummies came into the collections of most museums in the late 19th century and early 20th century, they were dated and sexed based on the coffin the mummy was found in. We now know that rampant reuse of coffins means these assumptions may be wrong.”

Asyut - a place where the unknown woman once lived - was at the crossroads of several trade routes. It was rich in culture but, because of all those roads, vulnerable to attack, and therefore protected by well-armed soldiers. Asyut lay just below a constriction in the river that allowed Asyut officials to stop traders carrying cargo downstream to the cities of the north and extract tolls from them.

A 3,200-year-old Egyptian mummy arrives Nov. 24 at the School of Medicine to undergo a CT scan. Norbert von der Groeben

Asyut also lay at the north end of the infamous Darb el-Arba`īn, the Forty Days’ Road, coming through the desert from Darfur; the 1,100-mile road was a major route for trading gold, ivory, spices, animals — and people. Until well into the 18th century, millions of slaves were forced to walk out of Africa on the Darb el-Arba`īn.

There is very little known about Hatason, in fact, the museum still wasn’t positive that she was a woman, or how ancient she was. Even her name is an invention.

“This mummy is known historically as Hatason,” said Jonathan Elias, PhD, director of the Akhmim Mummy Studies Consortium. “That is not her name. That is a corruption, we believe, of the name of a famous queen, Hatshepsut.” Private collectors of the 1890s liked to think they were purchasing royal mummies. Salesman likely named the mummy Hatason to make her sound like a queen.

Was she the same age as the coffin she has been stored in?

Egyptian city of Asyut is an old city which was first in pharaonic times, then the capital of the Thirteenth Nome of Upper Egypt and named Syut. Later, the Greeks renamed it Lycopolis which means 'city of the wolf'. This was due to the importance of the Jackal gods Wepwawet (Opener of Ways) and Anubis.

Or could it have been from an earlier or later period?

The scans revealed that Hatason’s brain was still inside her skull, but it was resting atop a pile of dark matter he said was probably sediment.

“It’s some form of material added into the brain case while the brain was left inside,” he said. “We have not seen that particular pattern before.”

The bones of her nose were intact, indicating that no one had even tried to remove her brain. Elias said the sediment was likely injected into her skull on purpose.

But why?

A thousand years later, he said, it would have been standard to remove the brain. In Hatason’s time, mummy experts seemed to have been experimenting with preservation techniques.

The size of the skull, however, suggests that this was indeed a young woman. thinks this mummy dates to the New Kingdom period, between the sixteenth and eleventh centuries B.C.

“What would convince you that the mummy is New Kingdom?” Müller asked Elias, referring to the period in Egypt between the 16th and 11th century B.C. The way the mummy was prepared, said Elias. “The fact that there was no excerebration [removal of the brain]. In mummies manufactured after a certain time, there is excerebration almost 100 percent of the time. But we have no excerebration,” he said.

It will take some weeks to process the images, study them further and think about what they say about Hatason and the history of mummies generally, Elias said.

“There are not that many mummies from this era that have been researched,” he added.

Soon though, a company that specializes in three-dimensional imaging and museum exhibits will work with the Legion of Honor on a special exhibit to display Hatason and a 3-D model of the mummy next spring.

AncientPages.com

source: Stanford Medicine