Location Of Elusive Spanish Fort Is Now Verified By Florida And Georgia Archaeologists

Conny Waters - AncientPages.com - The location of Fort San Antón de Carlos, home of one of the first Jesuit missions in North America has been now verified by Florida and Georgia archaeologists.

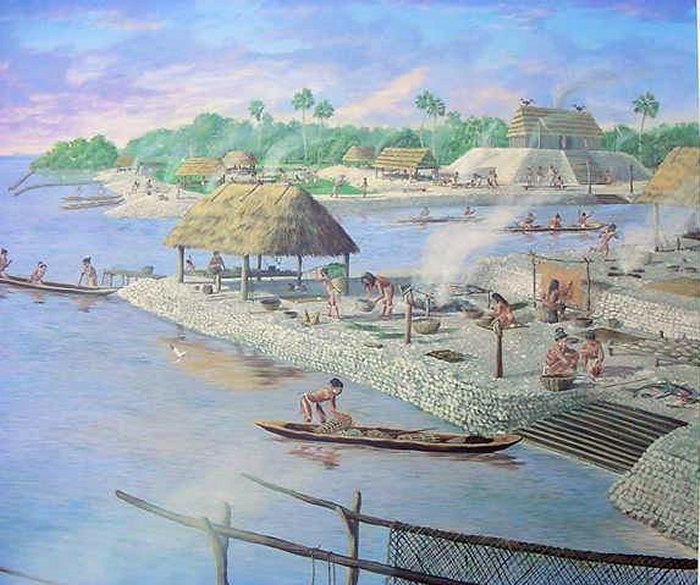

Calusa Indians used hundreds of millions of shells.

Calusa Indians used hundreds of millions of shells.

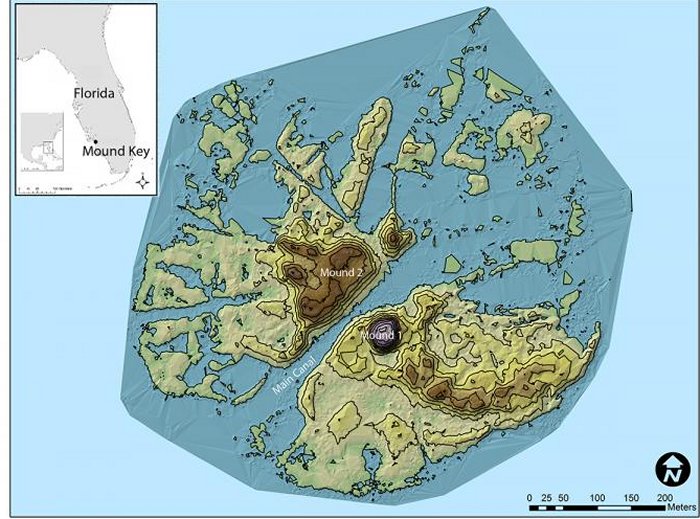

The Spanish fort was built in 1566 in the capital of the Calusa, the most powerful Native American tribe in the region, on present-day Mound Key in the center of Estero Bay on Florida's Gulf Coast.

Researchers have been searching for concrete evidence in the area since 2013. They have long suspected that the fort, named for the Catholic patron saint of lost things, was located on Mound Key.

"Before our work, the only information we had was from Spanish documents, which suggested that the Calusa capital was on Mound Key and that Fort San Antón de Carlos was there, too," said William Marquardt, curator emeritus of South Florida archaeology and ethnography at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

See also:

Secrets Of Mysterious Lost Kingdom Of Calusa In Florida And The Shell Indians

Florida’s Ancient Calusa Kingdom Developed Sophisticatedly Engineered ‘Watercourts’

"Archaeologists and historians had visited the site and collected pottery from the surface, but until we found physical evidence of the Calusa king's house and the fort, we could not be absolutely certain."

Spanish historical records named Florida's Mound Key, the capital of the Calusa kingdom, as the site of Fort San Antón de Carlos, home of one of the earliest North American Jesuit missions. Archaeologists have now uncovered evidence of the fort on one of the island's shell mounds. Image credit: Victor Thompson

Spanish historical records named Florida's Mound Key, the capital of the Calusa kingdom, as the site of Fort San Antón de Carlos, home of one of the earliest North American Jesuit missions. Archaeologists have now uncovered evidence of the fort on one of the island's shell mounds. Image credit: Victor Thompson

The Calusa were one of the most politically complex groups of fisher-gatherer-hunters in the world and resisted European colonization for nearly 200 years, Marquardt said. They are often considered to be the first "shell collectors," using shells as tools, utensils, and jewelry and discarding the fragments in enormous mounds. They also constructed massive structures known as water courts, which acted as fish corrals, providing food to fuel large-scale construction projects and a growing population.

The Calusa kingdom controlled most of South Florida before being devastated by European disease.

Researchers believe that by the time the Spanish turned Florida over to the British, any remaining Calusa had already fled to Cuba.

Researchers continue to question how the Spanish survived on Mound Key and met their daily needs despite unreliable shipments of minimal supplies from the Caribbean and strained relations with the Calusa - whose surplus supplies they needed for survival. The only Spanish fort known to be built on a shell mound, Fort San Antón de Carlos was abandoned by 1569 after the Spaniards' brief alliance with the Calusa deteriorated, causing the Calusa to leave the island and the Spanish to follow shortly after.

Researchers found Spanish artifacts such as a lead-shot mold, a hand-wrought spike and ceramics at Mound Key. Credit: Amanda Roberts Thompson

"Despite being the most powerful society in South Florida, the Calusa were inexorably drawn into the broader world economic system by the Spaniards," Marquardt said. "However, by staying true to their values and way of life, the Calusa showed a resiliency unmatched by most other Native societies in the Southeastern United States."

The fort is also the earliest-known North American example of "tabby" architecture, a rough form of shell concrete.

"Tabby," also called "tabbi" or "tapia," is made by burning shells to create lime, which is then mixed with sand, ash, water and broken shells. At Mound Key, the Spaniards used primitive tabby as a mortar to stabilize the posts in the walls of their wooden structures. Tabby was later used by the English in their American colonies and in Southern plantations.

the team uncovered a substantial amount of the walls they found, it is still only a small sample of the entire fort, and there is still much more to learn and excavate.

"Seeing the straight walls of the fort emerge, just inches below the surface, was quite exciting to us," Marquardt said. "Not only was this a confirmation of the location of the fort, but it shows the promise of Mound Key to shed light on a time in Florida's - and America's - history that is very poorly known."

Written by Conny Waters - AncientPages.com Staff Writer