Ancient Artifacts Hidden Beneath The Ice In Danger As Glaciers Are Melting

Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com - Glacier archaeology has become a sparking a brand-new field of research, and with good reason.

Over the years, archaeologists have unearthed exceptional artifacts hidden beneath the thick ice in the Alps. These ancient troves have changed our understanding of hunters and gatherers in the Mesolithic era, some 9,500 years ago.

The melting of the ice has offered an opportunity" to dramatically expand understanding of mountain life millennia ago, but to archaeologists, climate change is also a threat.

Unless the artifacts can be found quickly, they will be destroyed. Currently, these ancient objects are protected by thick layers of ice, but organic materials freed from the ice rapidly disintegrate and disappear.

Left: A Celtic artifact from the Iron Age representing a human-shaped statuette discovered in the Arolla glacier. Credit: AFP - Right: A laced shoe found with the remains of a prehistoric man dating back to around 2,800 BC. Credit: AFP

Archaeologist Regula Gubler told AFP “it is a very short window in time. In 20 years, these finds will be gone and these ice patches will be "It is a bit stressful."

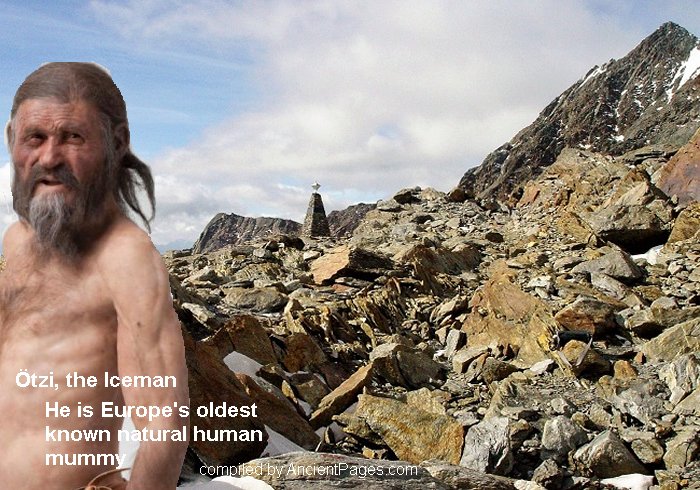

“The first major ancient Alpine find to emerge from the melting ice was the discovery in 1991 of "Öetzi", a 5,300-year-old warrior whose body had been preserved inside an Alpine glacier in the Italian Tyrol region.

When discovered Ötzi’s mummified body captured the attention of the world. His body was frozen alongside his clothing and gear, as well as an abundance of plants and fungi.

Today, 23 bryophyte species live in the area near where Ötzi was found, but inside the ice, the researchers identified thousands of preserved bryophyte fragments representing at least 75 species. It is the only site of such high altitude with bryophytes preserved over thousands of years.

Theories that Ötzi may have been a rare example of a prehistoric human venturing into the Alps have been belied by findings since of numerous ancient traces of people crossing high altitude mountain passes.”

Needless to say, that the body of Ötzi is not the only discovery scientists have made while investigating what could be hidden beneath the ice.

Just recently, Gubler and her team found a knotted string of bast, or plan fibres believed to be over 6,000 years old.

“The Schnidejoch pass, a lofty trail in the Bernese Alps 2,756 meters (9,000 feet) above sea level, has for instance been a boon to scientists since 2003, with the find of a birch bark quiver—a case for arrows—dating as far back as 3000 B.C.

Later, leather trousers and shoes, likely from the same ill-fated person, were also discovered, along with hundreds of other objects dating as far back as about 4500 B.C.” AFP reports.

In 1999, two hikers “stumbled across a wood carving on the Arolla glacier in southern Wallis canton, some 3,100 meters above sea level, they picked it up, polished it off and hung it on their living room wall.

It was only through a string of lucky circumstances that it 19 years later came to the attention of Pierre Yves Nicod, an archaeologist with the Wallis historical museum in Sion, where he was preparing an exhibition about glacier archaeology.

He tracked down the 52-centimeter-long human-shaped statuette, with a flat, frowning face, and had it dated.

A 17th-century pendant found in a glacier in the southern canton of Valais. Credit: AFP

It turned out to be over 2,000 years old—"a Celtic artifact from the Iron Age," Nicod told AFP, lifting up the statuette with gloved hands.

Its function remains a mystery, he said.

Amid surging temperatures, glaciologists predict that 95 percent of some 4,000 glaciers dotted throughout the Alps could disappear by the end of this century.

Scientists say the situation a race against the clock and an archaeological emergency.

But what can be done to preserve the artifacts? Climate change is a natural process we can not stop.

See also: More Archaeology News

Marcel Cornelissen, who headed an excavation trip last month to the remote crystal site near the Brunifirm glacier in the eastern Swiss canton of Uri, at an altitude of 2,800 metres (9,100 feet) says the understanding of glacier sites' archaeological potential had likely come "too late".

“We need to urgently sensibilise populations likely to come across such artifacts,” Nicod said.

Written by Jan Bartek - AncientPages.com Staff Writer